The slight man with tears running down his cheek had come to Woodhull Hospital in Brooklyn to visit his newborn son, Anuel, in the neonatal intensive care unit and plead for permission to take him home.

“You got me feeling like you all are holding my kid hostage,” said the man, Jose Perez, to a hospital social worker.

The social worker, according to an audio recording, explained yet again why the baby had to stay: The hospital needed additional proof Mr. Perez was the father. “Because mom is not present, you were unable to sign the birth certificate,” she said.

Not present.

The mother, Christine Fields, had not been present for more than a week. Mr. Perez, her fiancé, had been by her side as she bled to death in the hospital after giving birth.

Ms. Fields’s birth plan had declared him the father, but, critically, she had died before filling out a birth certificate. And with no official document, the hospital would not let him take his son home.

“You all don’t know how you all are making me feel,” Mr. Perez told the social workers. He told them about the couple’s two other children, Liam, 5, and Nova, almost 3: “They’re asking me for their baby brother.”

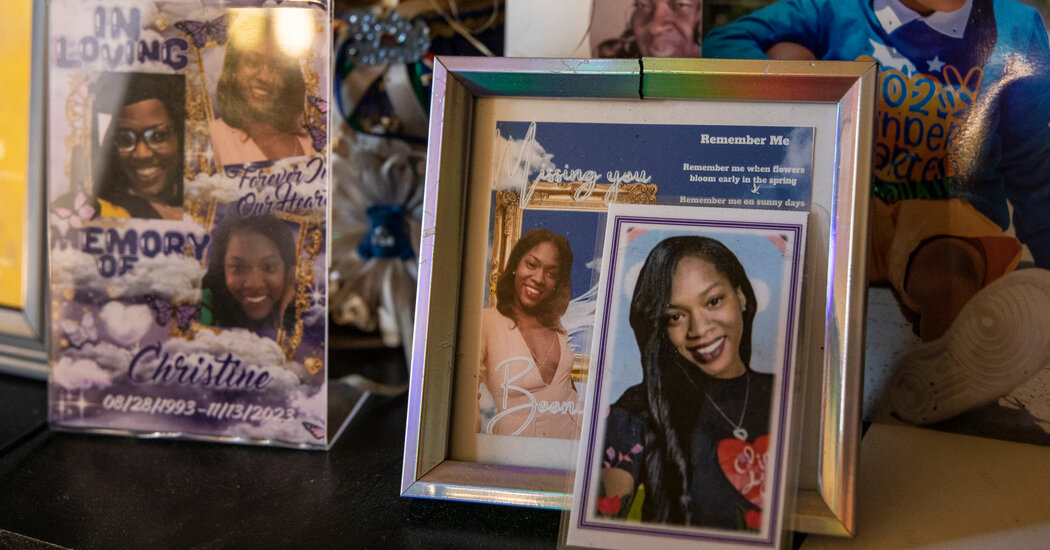

Ms. Fields’s death at Woodhull at age 30 sparked public protests and brought renewed public attention to New York City’s maternal health crisis. But privately, her death has exacted an even deeper toll, shattering a family that was once close. Her loved ones are turning against each other. And her children, raised as siblings, have been separated.

Mr. Perez’s efforts to find justice for his partner and provide some sort of normalcy for his children have led him through New York’s byzantine and often sclerotic court system. He has become a litigant in four different courts, as he tries to establish paternity, keep his children together, fight a landlord who has evicted the family from Ms. Fields’s apartment and obtain public benefits for his children.

Now, Mr. Perez, 42, and Ms. Fields’s mother, Denene Witherspoon, are locked in competition over who will raise the children. And whoever gains custody will also be likely to have some control over what will probably be a substantial amount of money: After Ms. Fields’s death, Mr. Perez and Ms. Witherspoon also jointly filed a $40 million lawsuit against the city’s public hospital system.

Their dispute has grown uglier by the day. Mr. Perez has kept his children away from the rest of the family. Ms. Fields’s relatives have denigrated him on social media and threatened to call child protective services on him.

“It was over money,” Mr. Perez said.

Mr. Perez and Ms. Witherspoon were once so close he called her “ma.” Ms. Witherspoon wrote to him on Facebook to say she loved him unconditionally.

But six months after Ms. Fields’s death, they barely speak, and one government system after another is failing the Fields family.

When Mr. Perez and Ms. Fields began dating five years ago, Mr. Perez was a 36-year-old widower, raising two teenage sons. His partner of two decades had died from thyroid cancer the year before.

Ms. Fields, then an acquaintance from the neighborhood, had given him a hug and offered her condolences at a corner store in Bedford-Stuyvesant, near where they both lived. She was struggling, too. She was raising Liam, who has dwarfism and a number of related medical issues, on her own and coping with depression. Mr. Perez stepped in to help, taking Liam for pizza and to the playground.

The couple had a baby daughter in December 2020 and named her Nova.

At first, they lived with Ms. Fields’s family. Then in April 2023, they moved to a new three-bedroom apartment overlooking the East River, in Long Island City, Queens. They could never have afforded it on what Mr. Perez made as a mover, or what Ms. Fields made arranging rides to help people get to medical appointments. But Ms. Fields had won a city-administered housing lottery.

“When you are FAITHFUL the lord blesses you in ABUNDANCE!” she wrote in a message to herself on her phone. Life was full of promise. Engaged since 2021, they began to look for wedding venues. Ms. Fields graduated from Monroe College with a degree in criminal justice, and she was pregnant again.

She chose Woodhull Medical Center, a massive structure near the elevated tracks of the J and M trains, to give birth. It is one of 11 city-run public hospitals. Ms. Fields had heard about a woman killed by a doctor’s mistakes during an emergency C-section there in 2020 and was apprehensive, Ms. Witherspoon later said.

But Ms. Fields herself had been born there, and so had Liam and Nova. Unlike many hospitals, this one had a labor and delivery floor with a cadre of midwives who promised a more natural birth experience.

But as she labored, the baby’s heart rate began to drop. Doctors told her she needed an emergency C-section. After Anuel was born, Ms. Fields said she felt strange. Then she grew quiet and seemed confused. “Christine, the baby is here,” Mr. Perez said. “It’s a boy!” No answer.

He tried to find ice to put on her lips, and told a nurse something was wrong. The next thing he knew, doctors and nurses had crowded around her. Someone was doing chest compressions.

And then she was dead.

A Void

When a baby is born, it is the mother who fills out the birth certificate forms. And when an unmarried mother dies in childbirth, the baby remains in limbo until paternity and custody can be otherwise established. (Maternal deaths are rare: Each year about five mothers die during childbirth or within hours of it in New York City, and a similar number die within the first week.)

In Mr. Perez’s case, no one disputed paternity. Ms. Fields’s detailed birth plan, which she gave to the hospital, listed him as the father. But for days after the birth of Anuel — named in honor of both Mr. Perez’s father and the Puerto Rican rap artist Anuel AA — Mr. Perez could only visit him in the intensive care unit. He often went after midnight, to hold his newborn and tell him “mommy loves you.”

At home, he had yet to tell Liam and Nova that their mother had died. They thought she was resting at the hospital. Nova’s princess-themed birthday party was coming up. She wanted to know if her mommy would be able to come.

The hospital declined to tell him what exactly had gone wrong and how Ms. Fields had died. The night of her death he had punched a door at the hospital in anger and grief, leaving his hand bruised and discolored for weeks. He ordered a black hooded sweatshirt with white lettering: “Woodhull Hospital Center Murdered Christine Fields,” and wore it when he joined a protest with Ms. Witherspoon and several maternal health activists in front of the hospital.

Not knowing the facts created a void that Mr. Perez filled with guilt. Had he been selfish to start a new family after his longtime partner had died? The same thought plagued him over and over: Maybe he was to blame? If he had kept his distance from Ms. Fields back in 2019, this would not have happened.

“Maybe if I wouldn’t have gone out with her, Christine would still be here,” he reflected recently.

If he was thinking these thoughts, maybe Ms. Fields’s family was thinking them, too. He told Ms. Witherspoon that he would understand if she blamed him.

On Nov. 24, 11 days after Ms. Fields’s death, Mr. Perez brought Anuel home after a family court judge granted him temporary custody. Ms. Witherspoon had vouched for him. On Nov. 28, the funeral procession for Ms. Fields set off. At its head were two horses, festooned with white plumes, pulling a carriage with Ms. Fields’s coffin.

A few days later, Mr. Perez and Ms. Witherspoon stood next to each other again and announced they would be suing the city over Christine’s death, demanding $40 million. Any payout would go to the children. Whoever was raising them would have some control over the money.

“Now I have to help raise three kids that don’t have a mother,” Ms. Witherspoon said, rushing through her words as she began to cry. “I miss my daughter so much, and I need to know what happened to my daughter.”

About a week after the lawsuit was announced, Mr. Perez dropped by Ms. Witherspoon’s apartment to pick up Liam, whom she was watching for the day. She told Mr. Perez to have a seat. Liam wouldn’t be going home with him.

Mr. Perez said he cried and reminded her that he had helped raise Liam.

“You’re always going to be Liam’s father,” Ms. Witherspoon said, according to Mr. Perez. “But we’re keeping Liam,” she added.

Mr. Perez thought about ignoring Ms. Witherspoon and bringing Liam back with him anyway. But he worried that a confrontation would result in her calling the police and his losing custody of Nova and Anuel.

“It was the hardest thing,” he said. “I lose Christine, I lose Liam.”

Ms. Witherspoon, a grandmother of 14, set up a bedroom for Liam adorned with his favorite character, Sonic the Hedgehog. In the living room, she had placed a life-size cardboard cutout of his mother — smiling and wearing a colorful dress — to watch over him.

Ms. Witherspoon has a gentle way with Liam. When the boy is being rambunctious, she talks to him as though he were the video game character he loves.

“Calm down Super Sonic,” she says, knowing that Liam must take more care than most boys his age: His bones are fragile, a result of dwarfism.

In an interview, she expressed bewilderment that Mr. Perez was angry at her. He seemed overwhelmed, she said, and she was trying to help him.

“I took Liam, but he has two other children, and I don’t want to put that burden on him,” Ms. Witherspoon said. “So I’m trying to help him. But in the midst of helping, he thinks that I’m trying to hurt him.”

Like Mr. Perez, she also acknowledged that the lawsuit — and the prospect of money — may have played a role in their falling out. “As soon as the thing came up with money, everything changed,” she said.

And while Mr. Perez lost a partner, Ms. Witherspoon lost a child.

“Every day I’m still trying to make sense of it. I’m still grieving. Every day I’m waking up without my daughter,” she said. “I’m missing who she was and what she could have been. ”

By December state investigators concluded that a troubling lapse by the obstetrician who delivered Anuel had led to Ms. Fields’s death. The doctor was quietly fired that month. In February, Mr. Perez returned home to their Long Island City apartment to discover that the landlord had changed the lock. He filmed his confrontation with building management. “You locked my kids out of the apartment,” he said. “That’s not right. You can’t do this.”

Management told him that the lease was not in his name.

He, Nova and Anuel moved in with his oldest two boys, Jordan and Jose Jr., who are in their 20s and live in Bushwick, Brooklyn. The apartment was neat but small. In the living room, one corner was full of photos of Teresa, the boys’ mother, who died in 2018. Another corner was a shrine to Christine.

A Legal Labyrinth

Mr. Perez had little legal claim to raise Liam. Instead, he focused on other urgent issues: cementing his status as the father and sole guardian of Nova and Anuel, and getting the apartment back.

It meant traveling what felt like a never-ending circuit among government offices.

He had to pay $300 when he took Anuel to a pediatrician visit. But for Anuel to be covered by Medicaid, the baby needed a Social Security number, which was proving impossible with the provisional birth certificate that referred to him as “No Given Name Fields.” Soon Mr. Perez had two different proceedings underway in Family Court in Brooklyn: one to establish that he should have custody of Anuel and another to establish he was his biological parent, which required a DNA test.

The eviction led them to housing court in Queens, to argue that the family had a right to the apartment in Long Island City. The judge there noted that because Baby Anuel’s birth coincided with his mother’s death, he had no claim to his mother’s apartment. “Child three, unfortunately, is due to the circumstances, not able to show 30 days’ occupancy,” the judge said.

The other children might have legal right to the apartment. Nova had lived there for nearly a year. But the judge was uncertain about Mr. Perez’s parental authority over Nova.

To establish that he was Nova’s father, too, Mr. Perez had to travel to a different courthouse, in Queens, and start another pair of cases. To bolster his custody claim, he got a DNA test for Nova. But this caused a setback when the housing court judge assumed Mr. Perez was trying to contest paternity, rather than affirm it.

It would take months to sort out the apartment. For starters, Mr. Perez had competition. Ms. Witherspoon also wanted it. Ms. Witherspoon said that as her daughter’s due date approached last year, Ms. Fields had invited her mother to move in to the third bedroom to help with the children. Ms. Witherspoon said she believed it would have been her daughter’s wish that she get the apartment.

“I had my bags packed when she went to the hospital,” Ms. Witherspoon said.

In addition to family court and housing court, Mr. Perez had a case in Surrogate’s Court to sort matters following Ms. Fields’s death, along with the wrongful death lawsuit in State Supreme Court in Brooklyn.

His predicament illustrated how unusually tangled and byzantine New York’s legal system is, said Adam Meyers, a housing court lawyer representing Mr. Perez. He said that other states had simpler, streamlined systems. But in New York, he noted, the questions following a mother’s death — what would become of her children, her property and her legal claims against the hospital — each landed in a separate court.

“Jose is — or will soon be — in four different courts trying to deal with different angles of this problem,” Mr. Meyers said.

A Family Divided

Once inseparable, Nova, 3, and Liam, 5, had gone months without seeing each other. Nova had lost her mother and then, it seemed to her, her brother.

Whenever anyone left the apartment, she needed reassurance: Where were they going? When would they come back?

Sometimes she asked if her mother was ever coming home.

To Mr. Perez’s distress, Nova invented a game linking pregnancy and death. First she held her belly and announced she was pregnant. Then she threw her hands up and declared she was dead. Over and over again.

In March, according to Mr. Perez, someone in Ms. Witherspoon’s family called child protective services against him. The allegations — as the child welfare investigator told him — were that he was staying out way too late with the baby, that the fridge was empty and that he was an addict. He took a drug test, opened the fridge and told the investigator about the family dynamics. As far as he knows, he said, the investigation was closed in his favor.

In an interview, Ms. Witherspoon denied calling the child protective agency, the Administration for Children’s Services.

But there was growing rancor. “I didn’t call ACS on you but I am going to call and let them know a thing or two,” Ms. Witherspoon’s sister wrote on Instagram. On Facebook, Ms. Witherspoon said Mr. Perez had not contributed his share of expenses and was chronically broke.

“The whole family is in disarray, and we can’t come together,” Ms. Witherspoon said recently. “I don’t understand it.”

The family that had once been so close went months without seeing each other, separated by a wall of grief and mistrust and confusion.

But on Father’s Day weekend, there was a sign that the wall might not be insurmountable: Ms. Witherspoon invited Mr. Perez to visit.

Nothing that stood between them had been resolved. The lawsuit remains pending. The children still live apart. Christine is still gone.

But for a day, at least, they set all that aside.

In the cab ride on the way, Nova asked if Liam was really going to be there.

He was, and when Mr. Perez arrived he called out, “Daddy, Daddy!” to the only father he had ever known.

Ms. Witherspoon got to hold Anuel for the first time in five months. And then Mr. Perez took the children to the park where Liam and Nova chased each other up and down the slide.