jetcityimage

The last article I wrote about Tesla, Inc. (NASDAQ:TSLA) was 2 1/2 years ago. In it, I took a bullish view on the company as a business, noting strong demand for its vehicles, imminent production increases coming from the construction of factories in Berlin and Austin, and strong Operating Cash Flow. This provided ample internally generated capital for capex deployment. The only issue was the stock’s sky-high valuation of 156x TTM PE and 75x FWD P/E, which was based on an anticipated doubling of EPS over the next year. There was little doubt that Tesla would eventually grow into its lofty valuation. However, there was a lot of doubt whether its stock would continue on its upward trajectory, and this resulted in Tesla’s shares being given a Hold rating. Eventually, those doubts turned out to be well-founded, as the value of shares in Tesla has fallen 11% since the article’s publication.

Highlighted in the article was its competitive advantage over legacy automakers. It seemed as if Tesla was racing towards an all-electric future, while most legacy automakers were only grudgingly coming to accept the fact that the industry was changing. Legacy OEMs were making plans to migrate 100% of their production to electric, but their target dates for a full changeover of production tended to be at least a decade away, if not much longer. At the time, it seemed as if legacy auto was fading fast.

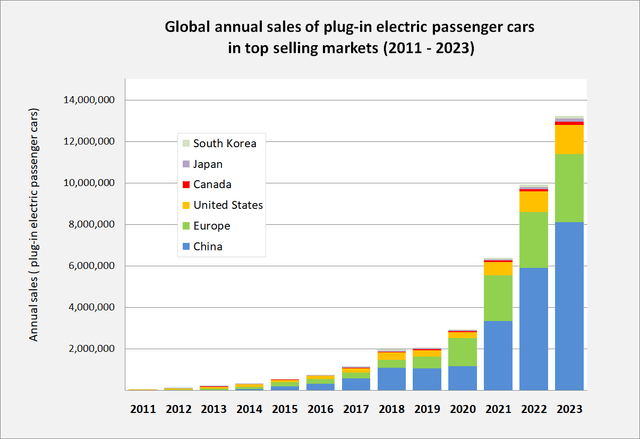

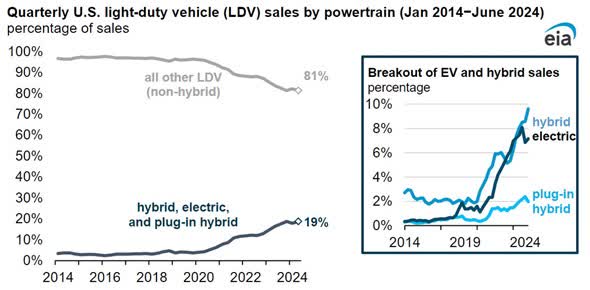

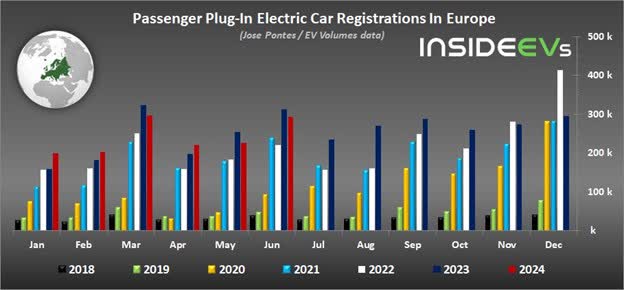

But 2.5 years is a long time in the automotive world. The electric vehicle (“EV”) market has definitely changed. As can be seen in the charts below, over recent months, sales of fully electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids have hit a rough patch in the US. Sales of hybrids, though, have continued to gain momentum, and monthly sales of EVs in Europe have faced outright declines on a year-over-year basis.

EIA.gov insideevs.com

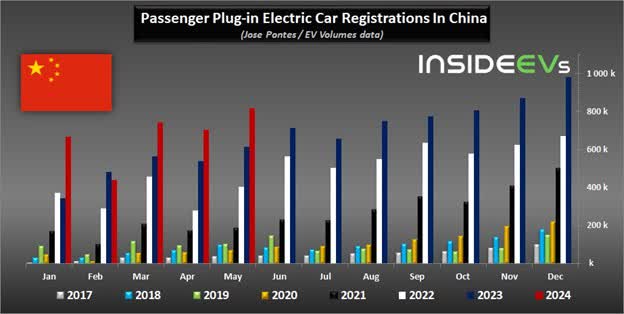

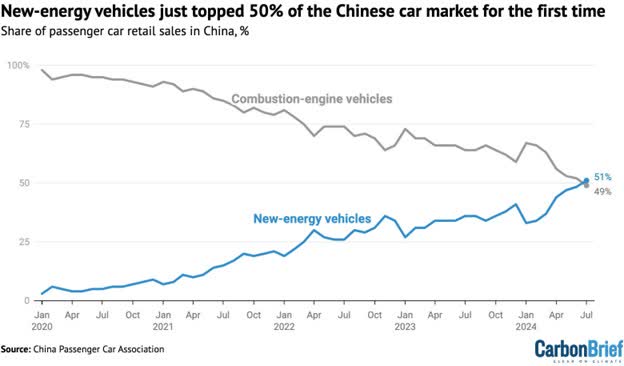

The declining trend has had one major exception: China. Despite the sluggishness being experienced in other markets, the Chinese EV market has kept chugging along as monthly sales continue to show impressive year-over-year gains. In fact, July was the first month that saw sales of plug-in vehicles outpace the sale of vehicles with traditional internal combustion engines (“ICE”) in the Chinese market. The graph below shows the speed at which this transformation has occurred.

insideevs.com carbonbrief.org

Trends in the Chinese car market, the world’s largest, may give Tesla bulls some respite. Tesla has a large factory in Shanghai, allowing it to take full advantage of this burgeoning market. The company has, in fact, benefited handsomely from China’s booming domestic market, selling almost 87k China-made cars in August, a 3% increase from a year earlier.

But the China EV story may not be so cut and dried. While continued strong growth in the Chinese market may be highly probable, it may cause Tesla some problems in the years to come. That’s because China’s EV enthusiasm and the government backing that comes with it are often attributed to environmental concerns. That may indeed be part of it, but what’s often left out are other factors that may lead Tesla to face much stronger competition in the future.

Industrial Policy

As mentioned, over the last decade, China has been on a relentless push to migrate the nation’s fleet from gasoline to electric power. As a consequence, EV sales have grown from almost nothing 10 years ago to over 8 million units last year, sales in China now account for about 60% of the world’s total EV sales. It’s followed by Europe, while the US is a distant third.

This impressive growth is not completely organic, however, as the Chinese government has, over the years, adopted several policies designed to encourage EV adoption. These ranged from per-vehicle subsidies on EVs to increased restrictions on ICE vehicles. The subsidies have not been trivial either; in fact, Beijing spent over $230 billion to support the EV industry over the past 15 years. Those funds went to both automotive companies and companies within the automotive supply chain, and it proved to be money well spent, as the sales numbers can attest.

The Chinese government appears to be well aware that China had a late start relative to other industrialized nations when it came to the production of globally competitive automobiles. Chinese OEMs would have a lot of difficulty carving out a place for themselves in the global ICE vehicle market. Therefore, it makes sense that the government would see the emergence of electric vehicles as a way to skip ICE altogether and begin producing vehicles on a platform that the world was eventually going to adopt anyway. Such a course of action would give China a valuable head-start in the development and deployment of EV technology. This very policy was articulated by China’s President, Xi Jinping, while visiting an electric vehicle factory in Shanghai in May 2014, when he said:

“Developing new energy vehicles is essential for China’s transformation from a big automobile country to a powerful automobile country. We should increase research and development, seriously analyze the market, adjust existing policy and develop new products to meet the needs of different customers. This can make a strong contribution to economic growth.”

This is not surprising, given that active government involvement in the automotive industry is a certainty in almost any nation. The auto industry and associated supply chains are worth trillions, employ millions of people throughout the world, and the location of production hubs can transform cities as well as provide nations with considerable industrial advantages. And given the Chinese government’s tight control over almost every sector of the country, it comes as perhaps little surprise that Beijing would pursue such an active and directed industrial policy.

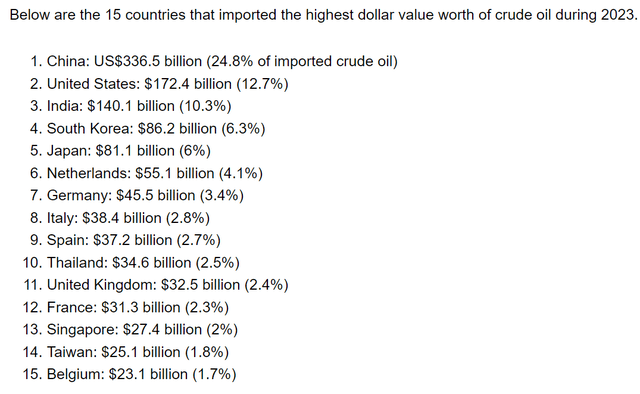

China’s Drive for Energy Independence

But of probably equal, if not much greater, importance to Beijing is the unstated benefit that domestic EV adoption brings. China’s economic ascent over the past 3 decades has seen it become the world’s largest importer of crude oil. As can be seen in the exhibit below, last year the nation imported well over $300 billion worth of crude to satisfy domestic demand, that’s almost a quarter of all the world’s imported crude oil.

And 70% of that crude went through the Strait of Malacca, a narrow maritime passageway between the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian island of Sumatra. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that more than 30% of global maritime crude is shipped through the Strait, the second most volume in the world after the Strait of Hormuz. It’s the shortest sea route between the oil-producing Middle East and the Chinese market, making it a key transit point for hydrocarbons imported into the country, as well as a glaring point of military vulnerability.

There is little doubt that China’s national security establishment is well aware of the threat posed by such a choke point. They know that any interference with energy flows could quickly result in the economy and military grinding to a halt. In 2003, then-President Hu Jintao spoke of the “Malacca Dilemma,” denoting the lack of transportation alternatives in case one of China’s geopolitical competitors implemented a naval blockade at the mouth of the Strait. And while the United States quickly comes to mind when discussing China’s adversaries, it should be noted that India, another country with which China has long-standing border disputes, is located near the Strait. For that reason, China has a strong geopolitical motivation for reducing imports of seaborne crude oil.

As mentioned above, every nation subsidizes its domestic automotive industry in some form or another. The US bailed out General Motors (GM) during the 2008 Financial Crisis, the Biden administration has expanded EV subsidies as part of its environmental agenda, and in Europe, subsidies are a given as they support many blue-collar jobs; however, the fact that China’s subsidies relate to a geopolitical imperative make them more existential in nature.

A political party in the US or Europe will lose blue-collar and working-class votes if it cuts automotive subsidies. However, if Beijing were to eliminate EV subsidies and stop or even slow the transition to electric vehicles, it could lose a future war.

The EV Capacity Buildout

The emergence of electric-powered vehicles was an opportunity for the Chinese government to foster an industry that would eventually greatly lessen the nation’s dependence on imported crude. It explains why Tesla was able to get special terms when it chose to build a factory in Shanghai while all other foreign companies expanding into the country were, at the time, required to partner with a Chinese firm. Tesla was exempt from this requirement and was allowed to set up a wholly owned Chinese subsidiary.

The aforementioned government subsidies also greatly helped to grow China’s domestic automotive industry and helped bring companies such as BYD (OTCPK:BYDDF), XPeng (XPEV), Geely Automobile (OTCPK:GELYF), and NIO (NIO), to national prominence. It helped foster fierce competition reminiscent of the US auto sector 100 years ago, with new companies and car brands regularly coming to market while uncompetitive ones quickly disappear.

bloomberg.com

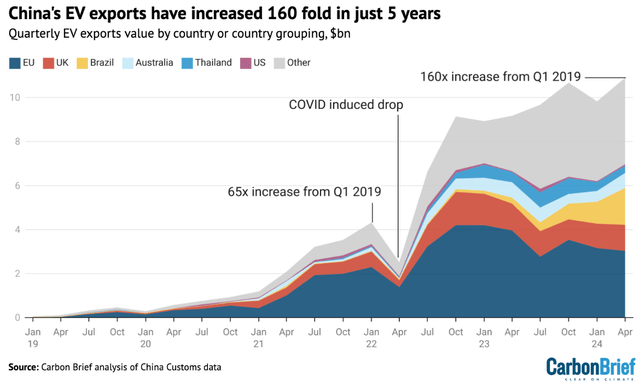

Favorable government policies, including ample subsidies, incentivized the Chinese EV industry to build as much production capacity as it could. This resulted in the addition of so much capacity that the domestic market could no longer absorb it all, and reports of fields and fields of abandoned EVs began appearing. In response, China’s EV companies logically turned to international markets in order to both cement their global leadership position in the EV space and export surplus production.

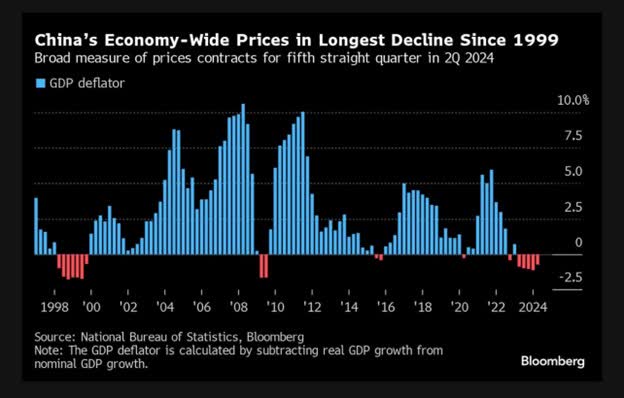

It’s worth remembering that EV production, both directly and indirectly, supports millions of people in China, and it’s easy to imagine that Beijing wants to see all of these people continue to be supported by EV production. Especially at a time when China’s economy is quickly slowing and has experienced outright deflation in the last 5 quarters. Beijing’s subsidized export-led EV strategy has therefore gone from a strategic initiative to an economic imperative.

Bloomberg.com

Just as China has economic and employment necessities, so do other nations. So, it was unsurprising to see a US and European response to China’s EV export growth strategy; after all, their auto industries also, directly and indirectly, employ millions of people and those industries have their problems, as evidenced by recent reports of Volkswagen’s (OTCPK:VLKAF) intention to close German factories. In May, the US responded to the surge of cheap imports from China by imposing a 100% tariff on all electric vehicles from China. Europe followed the US’s lead in June, although to a more limited extent, and in August, Canada imitated the US with its own 100% tariff on Chinese-made EVs.

Tesla

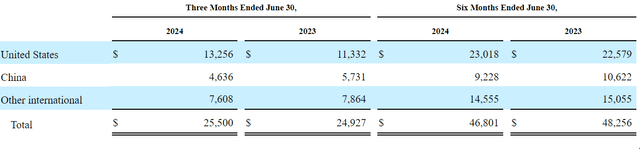

For its US division, these were positive developments for Tesla as almost half of its revenue came from the US market during the first two quarters of this year, although not all of that came from the automotive division. The stiff tariffs will neutralize the threat posed by Chinese imports and allow it to continue reigning as the top-selling EV brand in the world’s second-largest automotive market.

Tesla Revenue by Geographic Market (SEC.gov)

However, the problem lies with the world’s other automotive markets. As shown, Chinese OEMs are quickly moving into international markets such as Brazil, Australia, and Thailand.

This year, BYD has already overtaken Honda (HMC) and Nissan (OTCPK:NSANY) in total unit sales on a global basis as it added markets in Singapore, Mexico, and Japan. And it is even projected to overtake Tesla in the total number of EVs sold before the end of this year. Once it takes the lead it may not give it back as it has plans to build factories in Pakistan, Hungary, Brazil, and Turkey. Last week, BYD even increased its annual sales target to 4 million units from the previous 3.6 million.

The rapid pace of expansion has legacy automakers rattled as Jim Farley, CEO of Ford (F), noted the speed at which Chinese automakers are marching through international markets, labelling it an “existential threat.” There’s also the open question as to how long the tariff wall put up around Europe and the US will stand. The EU is already talking about reducing some of the tariffs it imposed just a few short months ago. The hard line adopted by both major political parties in the US before the November election may eventually give way to a more dovish stance with the change of administration.

Takeaway

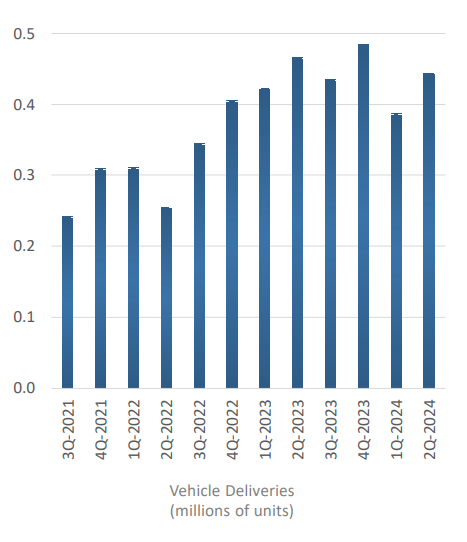

Meanwhile, Tesla is still priced for substantial growth. It currently trades at a 64x TTM PE and 98x FWD P/E while quarterly deliveries have hovered around the 400k unit mark for the last seven quarters. By comparison, BYD is trading at a much more conservative 19x TTM PE and 18x FWD P/E.

Tesla Q2 Investor Presentation

The valuation differential would be concerning in and of itself, but investors have to bear in mind that Tesla is not just competing with BYD. It is competing with the Chinese EV industry as a whole, which is backed by a government highly incentivized to create national champions in the EV space. Doing so will help Beijing prop up China’s faltering economy while liberating it from a decades-old national security constraint.

The automotive sector seems to oscillate between periods of relatively less government involvement and periods of more government involvement, and we seem to be in the latter. This introduces a higher degree of randomness, variability, politicization, and dependence on non-economic factors which complicate sales projections and valuation models. It also increases the risk for a stock as richly priced as Tesla’s, and for that reason, I continue to rate Tesla, Inc. stock a Hold.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.