Daniel Kramer, a photojournalist who captured Bob Dylan’s era-tilting transformation from acoustic guitar-strumming folky to electric prince of rock in the mid-1960s, and who shot the covers for his landmark albums “Bringing It All Back Home” and “Highway 61 Revisited,” died on April 29 in Melville, N.Y., on Long Island. He was 91.

His death, in a nursing home, was confirmed by his nephew Brian Bereck.

Rolling Stone magazine once described Mr. Kramer as “the photographer most closely associated with Bob Dylan.” But that designation seemed highly improbable at the outset.

Although Mr. Dylan had already begun his rise to global fame — he released his third album, “The Times They Are a-Changin’,” in early 1964 — Mr. Kramer knew little about him.

That changed in February 1964, when he watched the 22-year-old Mr. Dylan perform his rueful ballad “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” on “The Steve Allen Show.” The song details a real event in which a Black woman died after being struck with a cane by a wealthy white man at a white-tie Baltimore party.

“I hadn’t heard or seen him,” Mr. Kramer said in a 2012 interview with Time magazine. “I didn’t know his name, but I was riveted by the power of the song’s message of social outrage and to see Dylan reporting like a journalist through his music and lyrics.”

As a young Brooklynite trying to carve out a career as a freelance photographer, Mr. Kramer decided he had to arrange a photo shoot with the budding legend. He spent six months dialing the office of Mr. Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman. “The office always said no,” Mr. Kramer said in a 2016 interview with the British newspaper The Guardian. Finally, six months later, Mr. Grossman himself took his call. “He just said, ‘O.K., come up to Woodstock next Thursday.’”

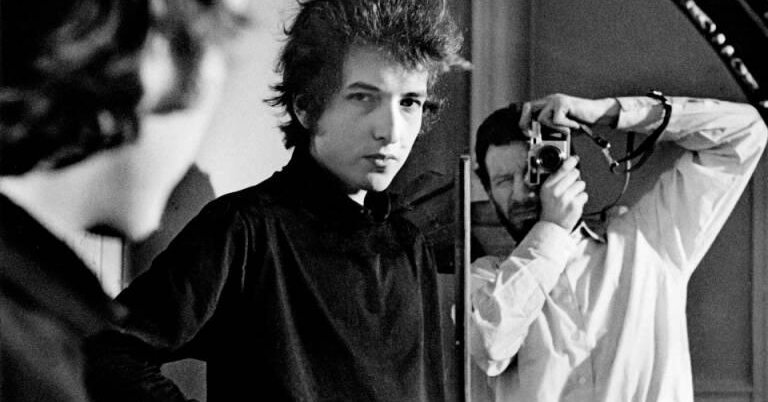

A one-hour shoot on Aug. 27 turned into a five-hour shoot, which turned into a 366-day photographic odyssey in which Mr. Kramer captured rare behind-the-scenes images of Mr. Dylan at home, on tour and in recording sessions as he was lighting the fuse that helped spark the countercultural explosion of the 1960s.

Soon Mr. Kramer’s Dylan images were popping up in publications around the world. Mr. Kramer published two collections, “Bob Dylan” (1967) and “Bob Dylan: A Year and a Day” (2018), which contained nearly 200 photos.

To Dylanologists, 1965 was the year of the big bang. In July, the future Nobel Prize winner shocked traditionalists at the Newport Folk Festival by ditching his acoustic guitar for a Fender Stratocaster, backed by a fully amplified band.

It was one of the most storied, and dissected, moments in rock history. “In most tellings, Dylan represents youth and the future, and the people who booed were stuck in the dying past,” Elijah Wald wrote in “Dylan Goes Electric!” (2015). “But there is another version, in which the audience represents youth and hope, and Dylan was shutting himself off behind a wall of electric noise, locking himself in a citadel of wealth and power.”

As Mr. Kramer later put it: “Bob didn’t really want to be Woody Guthrie. He wanted to be Elvis Presley.”

The photographer had his own quibble about this historical moment: At a shoot at a Columbia Records studio in New York for the seismic 1965 album “Bringing It All Back Home,” he had already witnessed Mr. Dylan plugging in and forging his own brand of rock ’n’ roll.

“People always say that Dylan went electric at Newport in the summer of 1965,” he told Rolling Stone. “Well, not to me he didn’t. I saw him go electric that January, when it was still snowing.”

Mr. Kramer also shot the cover image for the album. One of the most recognizable in rock history, it depicts a dapper Mr. Dylan seated with a cat on his lap in the living room of Mr. Grossman’s house near Woodstock, N.Y., surrounded by a jumble of magazines, record albums and a fallout shelter sign, with his manager’s wife, Sally Grossman, in a red dress, staring on from a sofa behind him. Mr. Kramer earned a Grammy nomination for the image.

Mr. Kramer later said that he took only 10 shots that day, and that the final image was chosen because it was “the only one in which the cat was looking at the lens.”

He also discussed the circular aurora effect overlaying the image, which lent it psychedelic overtones.

“People think I used Vaseline to create that circular image or that it’s a blur,” Mr. Kramer once said. “That’s not what I did. It’s two different pictures on one film. One is moved, and one is not. I wanted to simulate a record spinning or the universe of music.”

Later that year, Mr. Kramer shot the cover for “Highway 61 Revisited,” a casual candid showing Mr. Dylan, in a Triumph motorcycles T-shirt, seated on the stoop of the Manhattan building where his manager lived and flashing a vaguely menacing glare. “He’s almost challenging me or you or whoever’s looking at it,” Mr. Kramer recalled: “‘What are you gonna do about it, buster?’”

Mr. Kramer was born on May 19, 1932, in Brooklyn, the eldest of three children of Irving Kramer, a dockworker and amateur filmmaker, and Ethel (Berland) Kramer, a hospital administrator.

“At an early age I migrated to the camera,” he said in a 1995 interview with The New York Times. “By age 14, I had a one-boy show at the junior high school.

He worked as an assistant to the photographer Philippe Halsman, and to the team of Allan and Diane Arbus, in addition to studying at Brooklyn College and serving in the U.S. Army.

During his year with Mr. Dylan, Mr. Kramer was granted unrivaled access. In an interview published by Govinda Gallery in Washington, which mounted an exhibition of his Dylan photos in 1999, Mr. Kramer recalled a show at Lincoln Center in New York in October 1964, where the venue’s management informed Mr. Kramer that he would be restricted to a glass-enclosed balcony during the performance.

“So Bob said to his manager, ‘You tell them here that if he can’t do whatever he wants to do, I’m not going on,’” Mr. Kramer recalled.

Away from the stage, he managed to capture Mr. Dylan in rare moments of downtime — aiming a cue in an upstate New York pool hall, playing chess in a Woodstock cafe. One of his most famous shots from the period was a black-and-white portrait of Mr. Dylan in sunglasses, standing in front of the empty bleachers of Forest Hills Stadium in Queens before a concert on Aug. 28, 1965.

That shoot marked the end of Mr. Kramer’s run as Mr. Dylan’s de facto house photographer. “I didn’t want people to think that’s all I did,” he said.

Shooting portraits of luminaries for a variety of publications over the years, he maintained his ability to connect with them on an intimate level. “I’ve had a writing lesson from Norman Mailer, a boxing lesson from Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali, and a harmonica lesson from Bob Dylan,” he told The Times.

Mr. Kramer married Arline Cunningham in 1968. She died in 2016. No immediate family members survive.

While he was well aware that he was privileged to serve as a witness to pop music history, Mr. Kramer later said that the magnitude of what was unfolding before his lens was not always so apparent at the time.

“You don’t know someone’s changing the world,” he said, “until the world’s been changed.”