As a teenager in Queens, Mike Repole worshiped the great St. John’s University basketball teams of the 1980s, whose stars often came from the gyms and playgrounds of New York City.

The team’s tough, defensive brand of championship ball helped Repole, the son of an immigrant waiter and a seamstress, identify with the school. As a student there, he honed the grit that would help him amass a sports-drink fortune.

But as his star was rising, St. John’s basketball declined, with decades of disappointing seasons. Now, Repole’s money, which Forbes magazine estimates at $1.8 billion, has helped make St. John’s the nation’s sixth-ranked team, with top players acquired from around the nation.

It finished the regular season 27-4 and will be the top seed in this week’s Big East Tournament at Madison Square Garden. Fans have high hopes for a deep N.C.A.A. Tournament run after that.

Repole, 56, says the team is reclaiming its greatness.

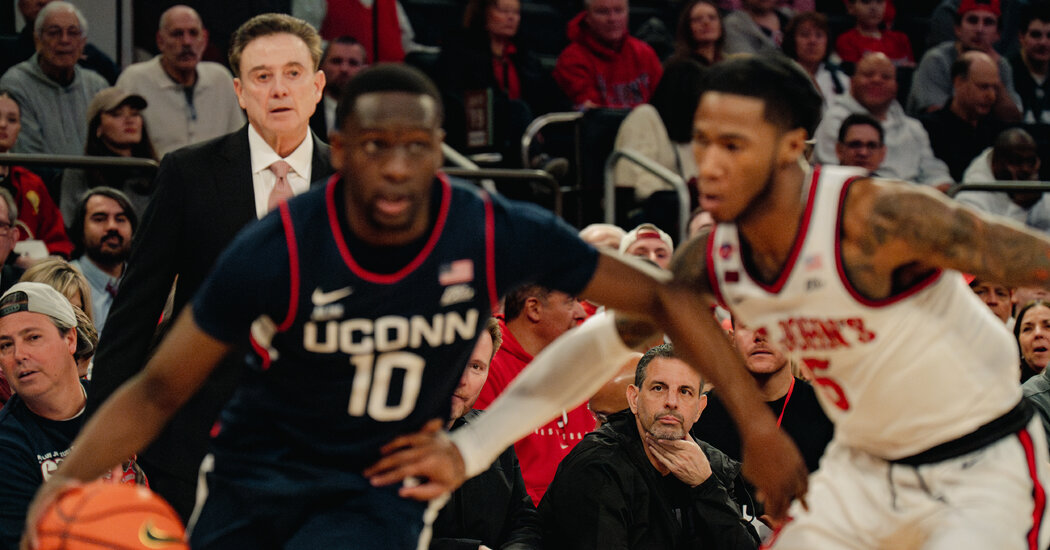

“It’s been missing for 25 years, and now to have it all back is pretty magical,” Repole said during a recent game at Madison Square Garden, where he arrives by private jet from his Florida home and sits courtside near head coach Rick Pitino.

With the St. John’s team’s success, Repole has emerged as one of the most striking examples of how money is reshaping college basketball.

His backing, which came after a falling-out with the school, was part of the reason that Pitino, a tarnished Hall of Fame coach, took over the team last season. The billionaire’s money has let Pitino acquire top transfers under new rules that allow college athletes — formerly constrained by the N.C.A.A.’s insistence on amateurism — to profit from their names, images and likenesses, known as N.I.L.

“The wild West,” Representative Gus Bilirakis, a Republican from Florida, called it during a congressional hearing last week.

Colleges that once courted and recruited high school players whom they kept for four years now browse an online marketplace known as a transfer portal that functions like professional free agency. Serendipity is scarcer, and alumni donors have become nearly as important as coaches.

St. John’s, thanks largely to Repole, now compensates its players like powerhouse programs. For his part, Repole jokes that St. John’s will be changing its name to St. Mike’s.

Last season, the school reached the Big East semifinals for the first time since 2000. This season, its home games are packed, whether at Carnesecca Arena on campus or at the Garden, where Repole recently cheered on the Red Storm as they beat the two-time defending national champion, the University of Connecticut.

The sold-out game was broadcast on national television. Spike Lee sat courtside. In the stands, fan after fan came up and thanked Repole, whose face floated over the student section in the form of a poster. The benefactor also materialized on an overhead screen along with an announcement of his matching fund drive for acquiring players, in which big donors can win dinner with Repole and Pitino.

At least half the St. John’s basketball N.I.L. budget is funded by Repole, who a year ago vowed to spend “whatever it takes.”

Between $3.5 million and $4 million has gone to pay players this year, according to Pitino. That would put it in the top 20 highest N.I.L. payrolls in the country, said Jason Belzer, a lawyer who often represents colleges in such deals.

The Supreme Court has sided with student-athletes seeking compensation beyond scholarships at big-time college programs that profit off them.

But the ensuing regulations are so unclear and untested that “guidelines on endorsements, payments and contracts make high-profile college sports and their star athletes resemble the show ‘Let’s Make a Deal,’” said John Thelin, an author and University of Kentucky professor emeritus who specializes in college sports.

Money now largely determines the success of a basketball program, and without further regulations, Thelin said, “the rich are truly going to get richer” by monopolizing top players.

The S in St. John’s, he quipped, might as well be a dollar sign.

Repole carries himself like someone who knows both ends of the economic spectrum. He is a trash-talking Everyman who favors workout gear and travels with a team of assistants. He has donated millions to nonbasketball causes at St. John’s and his companies’ products are advertised at games.

Repole revels in his new role as the super-booster in the ear of Pitino as the coach has quickly pulled together a winning unit out of new arrivals. Repole is a locker room regular and often blurts out his own plays during games. Speaking to business students on campus recently, he said he had always harbored a dream to coach St. John’s.

“And that came true last year,” he joked, before adding, “Oh, no, Rick is the coach.”

Repole told the students his work ethic was forged by playing basketball in Queens schoolyards against better players.

The energy of the 1980s teams of Chris Mullin and Coach Lou Carnesecca originally attracted Repole to St. John’s. But the team has qualified for the N.C.A.A. tournament only four times since 2000, without a single win.

As his team foundered, Repole got richer, by founding and selling Vitaminwater and Bodyarmor SuperDrink. Last year his sneaker and apparel company, Nobull, merged with TB12, the health and nutrition company co-founded by Tom Brady.

In an interview, Pitino called Repole a “Damon Runyon-type character” and a talented businessman.

Repole admired Pitino even as a teen, when the coach turned around a losing program at Providence College and took it to the Final Four in 1987. As a young entrepreneur, Repole said, he read Pitino’s self-help book “Success Is a Choice” and began applying its teachings to business.

The two met some 20 years ago when Pitino was coaching at Louisville. Repole began trying to get Pitino to St. John’s, a largely commuter school with about 15,700 undergraduates.

That did not seem likely. Pitino, 72, spent many years coaching at Kentucky and Louisville, winning a national championship at each.

But his 2013 championship with Louisville was vacated after an investigation found that an assistant coach had furnished players and recruits with escorts and strippers. Personal improprieties emerged during a 2009 criminal case against a woman who was found guilty of trying to extort Pitino after a sexual encounter.

Louisville ousted Pitino in 2017 after a widespread federal investigation into college basketball corruption that disclosed illicit payments to a Louisville recruit.

Pitino left big-time coaching and led a team in Greece before being hired in 2020 by Iona College, a small school just north of New York City. St. John’s came calling in 2023 after Pitino had led Iona to two N.C.A.A. tournament appearances in his three seasons.

Repole was at first an ancillary figure. St. John’s officials had soured on him. In a 2019 radio interview, he called the school’s culture toxic and derided its top officials as “incompetent, clueless leaders” and weak “puppets.”

And in the months before Pitino’s hiring, Repole had devoted an X account, @RepoletheSavior, to both salvage and troll the program, alternately mocking the St. John’s leadership and urging them to call him.

Despite the rancor, Pitino said he told reluctant St. John’s officials that luring top transfers would require Repole’s money. Pitino said he told the officials that if they failed to reconcile with Repole, “I think you guys would be missing out on a tremendous asset.”

“He was going to be 50 percent of our N.I.L. money,” Pitino said. “Without Mike Repole, we did not have the funds to do what we wanted.”

Pitino’s checkered history gave St. John’s pause. There was “some reputational risk,” the school’s president, the Rev. Brian Shanley, told The Associated Press at the time.

But an independent panel had recently cleared Pitino in the federal investigation at Louisville, and Father Shanley, as a priest leading a Catholic university, spoke of second chances and forgiveness for Pitino. He got the job.

“I don’t blame or fault a smaller institution with a lesser endowment for doing this,” said Thelin, the professor. “What other activity could give them this chance at visibility?”

Once hired, Pitino began shopping for transfers. He tapped Repole when funds ran low, and last year had the fourth-ranked recruiting class in the country, according to 247Sports, a college sports analysis site.

Pitino acquired the top transfer in Kadary Richmond, who left Seton Hall after helping lead the Pirates to the National Invitation Tournament championship. When Richmond faced his old school in January, Seton Hall fans booed him and mocked him with signs bearing dollar bills.

After the game, Pitino defended Richmond as a “free agent” who would have stayed at Seton Hall if only it had the revenue to match the St. John’s offer.

And Repole is back in good graces on campus. He told students there recently that despite his wealth, “I’ll always be Mike from Queens,” a guy who finally found a way to help his old college team regain greatness.

“It’s actually a dream,” he said, “40 years later.”