The conductor Gustavo Dudamel has premiered dozens of pieces in his career.

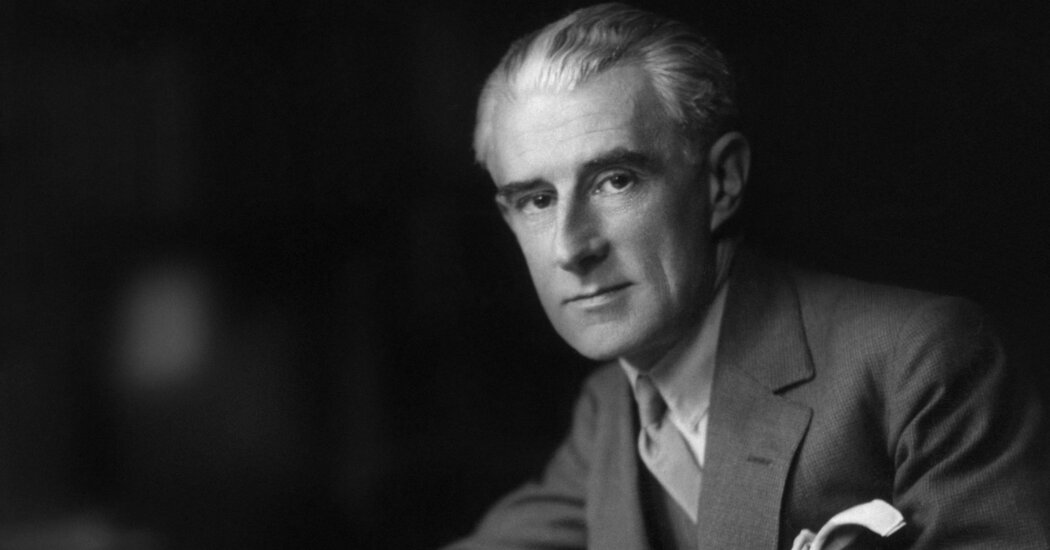

But the score that he was giddily studying on a recent afternoon at Lincoln Center was different: a nearly 125-year-old piece by the French composer Maurice Ravel that had only recently surfaced in a Paris library.

“Imagine more than 100 years later discovering a small, beautiful jewel,” Dudamel, the incoming music and artistic director of the New York Philharmonic, said in an interview at David Geffen Hall. “It’s precious.”

On Thursday, Dudamel and the Philharmonic will give the world premiere of the five-minute piece as part of a program celebrating the 150th birthday of Ravel, one of the leading composers of the 20th century, whose works include “Boléro,” “Le Tombeau de Couperin” and “La Valse.”

The newly found piece, “Sémiramis: Prélude et Danse,” was written sometime between 1900 and 1902, when Ravel was in his late 20s and sparring with administrators at the Paris Conservatory, where he studied piano and composition.

The work, from an unfinished cantata about the Babylonian queen Semiramis, reveals a young musician still honing his voice and looking to others, like the Russian composer Rimsky-Korsakov, for inspiration. “Sémiramis” lacks some of the lush textures and rich harmonies for which Ravel would become known — he was a master of blending French impressionism, Spanish melodies, baroque, jazz and other music — though there are hints of his unconventional style.

The manuscript, more than 40 pages long, includes an aria for tenor and orchestra that the Philharmonic will not perform; the Orchestre de Paris will premiere that section, alongside the prelude and dance, in December under the baton of Alain Altinoglu.

“Sémiramis” is a coup for the New York Philharmonic, which is gearing up for the start of Dudamel’s tenure in fall 2026. It is rare to uncover unpublished works by major composers, and Ravel, who died in 1937 at 62, wrote only about 80 pieces in his life, fewer than many of his peers.

Dudamel said the Philharmonic would do its best to capture Ravel’s intentions. The manuscript lacks a tempo marking at the start, and there appear to be some missing notes, including in the harp line.

“It’s more pressure,” Dudamel said. “The only thing I can hope for is that he will send a message to me secretly through my dreams.”

The discovery has energized the Philharmonic’s players, who with no recordings or scholarly notes to turn to, have consulted each other in recent days about dynamics and phrasing.

“It’s a pretty vulnerable moment for Ravel,” said Julian Gonzalez, the associate principal bassoon. “He’s not going to be at the rehearsals. He can’t change anything. It will be up to us to get it right.”

“Sémiramis” had been sitting in the archives of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France since 2000, when the library acquired it in an auction of Ravel memorabilia. But the manuscript was brought to light only recently, when researchers were looking for new works that could be performed to mark Ravel’s 150th birthday.

François Dru, the editorial director of the Ravel Edition publishing house, came across an image of the score while searching the library’s digital archives several years ago. He knew the name of the piece because it appeared in a catalog of Ravel’s works; the manuscript had been marked as “not traced.”

“It was very easy to find,” Dru said. “It wasn’t some of kind of adventure or mystery like Indiana Jones excavating something from the ground. I’m a bit amazed that nobody spotted it.”

Dru mentioned the score to Gabryel Smith, the director of the New York Philharmonic’s archives, when the two ran into each other at an exhibition about the Ballets Russes at the Morgan Library & Museum last year. But before bringing it to Dudamel, the Philharmonic wanted to be sure “Sémiramis” was authentic — the manuscript was unsigned and there were no references to public performances. It was possible, although unlikely, that Ravel had copied somebody else’s work as an academic exercise.

Verification came in the form of a diary from the Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes, a close friend and collaborator of Ravel’s.

In the diary, Viñes meticulously documented events at the Paris Conservatory and interactions with revered figures like the French flutist Paul Taffanel and the composer Gabriel Fauré, Ravel’s composition teacher and mentor.

Viñes wrote about the first read-through of the piece, which took place on April 7, 1902, during an orchestra class at the conservatory:

In the morning I went to the conservatory to hear Ravel’s cantata “Sémiramis,” which the orchestra read, studied and played under the direction of Taffanel; it is very beautiful and imbued with an Oriental flavor. The whole Ravel family was there, as well as Fauré and Juliette Toutain, Février, and Koechlin, etc!

The “Sémiramis” manuscript has certain Ravel hallmarks. The neat musical notation matches his penmanship, as does the handwriting, down to the “a” in “Danse,” which he wrote like the first letter of the Greek alphabet. And the musical style, heavily influenced by Russian masters, is consistent with some of the composer’s other early works, including his “Shéhérazade” pieces inspired by “The Arabian Nights.”

By the early 1900s, Ravel was already making his name as a composer, producing the beloved piano work “Pavane Pour une Infante Défunte” (1899) and other classics. Just two days before the “Sémiramis” reading at the conservatory, Viñes had given the premiere of “Jeux d’eau,” another cherished piano piece.

But despite his success, Ravel was an outsider at the conservatory, frequently clashing with its more traditionally minded professors. He repeatedly lost out on prizes, which were essential for survival at the conservatory. He was dismissed from the school several times for his lack of awards, only to return as an auditor in Fauré’s class. Around this time, he and his friends, including Viñes, formed Les Apaches, a society of writers, artists and musicians. They met weekly, sharing art and ideas, and greeting each other by whistling the opening melody from Alexander Borodin’s Symphony No. 2.

Ravel, who was born in France in 1875 to a Spanish mother and a Swiss father, might have written “Sémiramis” with the hope that it would be his prizewinning piece: The orchestration and style is notably conservative. But he appears to have abandoned the idea of a sweeping work; he left behind only the prelude, dance and aria.

Arbie Orenstein, a leading Ravel scholar, first came across a mention of “Sémiramis” in the 1970s, when he conducted research and interviews for his seminal biography, “Ravel: Man and Musician” (1975), He had found manuscripts of other unpublished Ravel works — including six that premiered for the composer’s centenary in 1975 — but had been unable to locate “Sémiramis.”

Orenstein said the work showed the composer’s early mastery of orchestration.

“He had already composed masterpieces, but he is still finding his way as a student,” he said. “On his way, he’s already there, in a sense.”

In the days before the premiere of “Sémiramis,” Dudamel and the Philharmonic’s players have been poring over the score, looking for connections to other Ravel works and for hints on questions of tone and timbre. Dudamel said he could hear early evidence of Ravel’s genius and echoes of later works like the “Ma Mère l’Oye” (“Mother Goose”) suite.

“Ravel creates perfumes of colors,” he said. “He is a colorist. He was creating such a beautiful and deep sensuality in music. I don’t think other composers have that touch.”

Dudamel said that while premiering “Sémiramis” was daunting, it was also an opportunity to shape Ravel’s music in an unexpectedly intimate way.

“The piece is still a mystery,” he said. “It is like an empty book for the imagination.”