The inaugural Indian Wildlife Ecology Conference (IWEC) 2024 was “ born from the collective aspiration of researchers and institutions in India to discuss the science of wildlife ecology, network and collaborate, and support the discipline’s growth.” as the website puts it. The three-day-long event, held at NCBS, Bengaluru, between June 14 –16, sought to be a platform “for the professional exchange of ideas and research findings, to encourage communication and collaborations across disciplines, and to promote professional growth and career development.” In keeping with this aim, the event saw several symposia, panel discussions and meetings occur, bringing together researchers in Indian wildlife ecology across taxa, landscapes, ecosystems, and disciplines.

Here is a brief of some of the conversations that took place at the conference.

Researchers present their findings on river ecology.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRAGEMENT

A panel discussion on AI and wildlife

“AI is everywhere…infiltrating our lives, whether we like it or not,” says scientist and social impact partitioner Sarika Khanwilkar. Sarika, who was recently moderating a session titled Artificial Intelligence and Wildlife Ecology Research, adds that she herself uses AI tools in her research. “I have an in-depth understanding of its merits and limitations,” she says.

These merits and limitations were discussed at large by the rest of the panel, comprising interdisciplinary researcher Akanksha Rathore, software engineer Alok Talekar, wildlife biologist MD Madhusudan and academician Saket Anand. Akanksha, who uses AI to study animal groups and their behaviour in the wild, says that the technology can be useful in making predictions that help decision-making. Artificial Intelligence, she believes, has the potential to take us in a good direction, if adopted judiciously, something Saket seems to agree with. “Machine learning and AI are tools that will help you if you use it right,” he says, adding that they could help with doing research more effectively.

Introductory Session of The Wildlife Ecology Conference 2024 at NCBS.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRAGEMENT

While the other panellists, too, agree on the merits of AI in research, they also bring up their concerns with this technology. “I often wonder about where technology stops and we enter the human domain,” says Madhusudan, while Alok believes that while AI has its uses, it cannot be a solution for everything. “We need a human in the loop somewhere for things that are sensitive,” he believes.

Also, as with any tool, it can and has been used for both good and bad things. Akanksha talks about how, while training guards in drone technology, she encountered one who wanted to use it in a somewhat unethical way. Since he was also a tour guide, he asked if he could use it to understand patterns when hyenas came out, she recalls, “These are all things that fall into AI ethics and concerns.”

Madhusudan, unlike the other panellists who appear to be carefully optimistic about the technology, is clearly an AI sceptic. “I am a biologist, and I still depend a lot on the old-fashioned human smarts that we have used,” he says, adding that even when looking at satellite imagery and so on, he relies on biological understanding and intuition. While not disputing the vast possibilities of AI, “he feels more comfortable questioning technology than the biology,” he admits.

More importantly, however, “both ecology and AI are situated in society and that society is a complex place,” he states, going on to question the point that technology and its tools are not intrinsically good or bad. While, for the most part, it is true that technology and tools assume the moral valency of their user, there is one fundamental difference with AI when compared to other technologies and tools since it is a direct reflection of the society that made it. AI, therefore, needs to have a moral compass, believes Madhusudan. “It has taken a large part of human history to realize that human life is precious, and all humans have value,” he says pointing out that AI also has the potential to learn inequality, prejudice, unfairness, deceit and greed. “Can we be sure that we are building something that does not hold a black mirror to us? This is an answer to which we can’t be completely sure of,” he says.

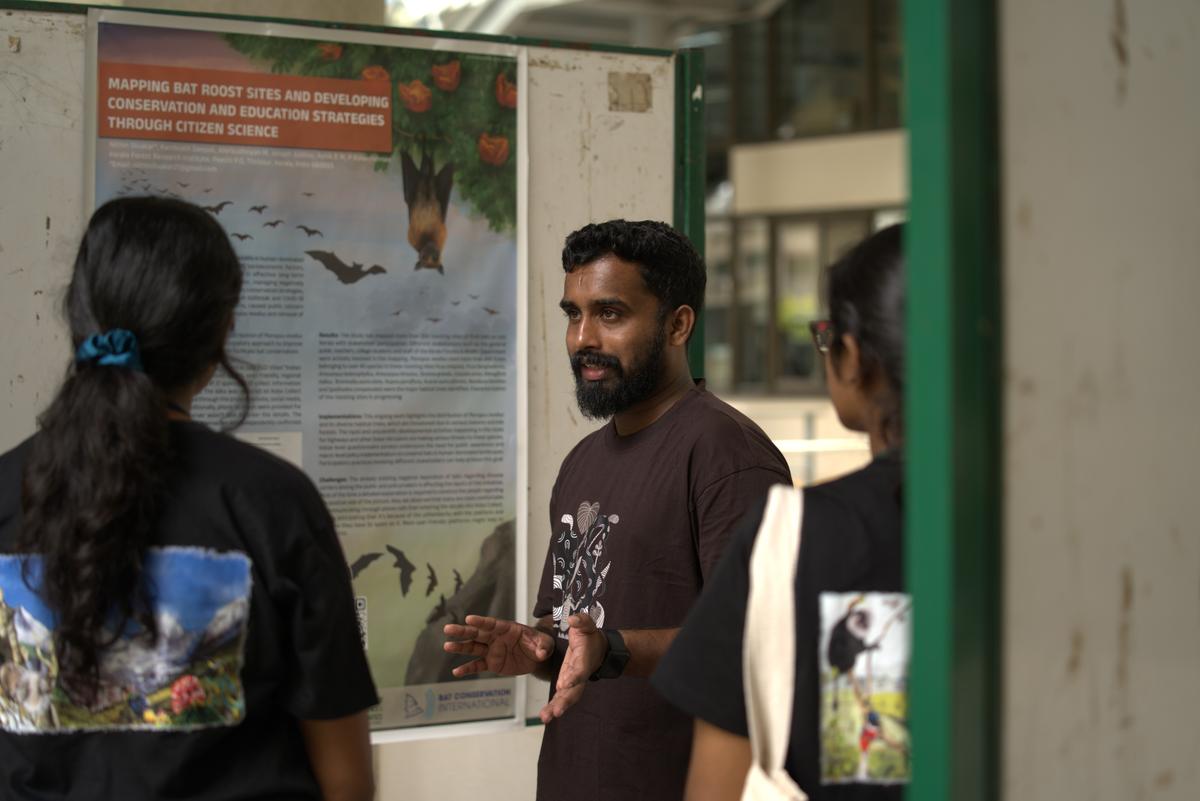

Participants displaying their research through vibrant posters.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRAGEMENT

Symposia on various aspects of ecology

Over these three days, several symposia took place, including those on plant phenology, small cats, raptors, marine flagship species, bat research, insects, and more.

Sneha Shahi, a PhD student, who was presenting a paper on river ecology spoke about the need for targeted restoration efforts in urbanized zones to safeguard river ecosystems. “We often forget to take into consideration the habitat assessment of these rivers” says Sneha Shahi, a PhD student, going on to talk about the ecological dynamics of a perennial river originating from the Agasthyamalai hills in Southern Tamil Nadu. She highlights the relationship between society and ecology, stressing the impact of human activities on river health and why we need to conserve these rivers.

Another aspect discussed at these symposia was the proliferation of the African sharp tooth catfish, which has been declared as one of fourteen highly invasive fishes identified in Indian waters. While the government of India has banned its rearing and selling, this catfish, known for its high adaptability, air breathability and rapid breeding, currently poses a severe threat to local biodiversity. Speakers proposed stringent measures to curb its spread and mitigate ecological damage, including the need for timely government intervention.

Stands and stalls displaying online portals (CEASE – protection against sexual harassment in the workplace).

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRAGEMENT

Preserving grasslands

Studies on the critically endangered Bengal Florican and the endangered Pygmy Hogs of Orang National Park were used to highlight the need for better grassland conservation efforts. In fact, even studying these animals was a task, says academician Karishma Sharma.“It (Bengal Florican) does not readily come out, and it has been a real pain to actually spot in the grassland for the past few days I have worked,” she says of this bird that faces severe habitat challenges, exacerbated by human activities like cattle overgrazing.

In the case of the pygmy hog, it has gone from critically endangered to endangered, according to researcher Jonmani Kalita. “It got a recovery boost by 8% from 2008 to 2015,” he says. Having said that, we have a long way to go in protecting these rare fauna, both of which are Schedule I species.

Campus was well decked out and on theme for the event.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRAGEMENT

Engaging displays

The conference also featured vibrant poster presentations showcasing diverse research initiatives across India, ranging from butterfly pollination patterns in West Bengal to the social dynamics amongst female elephant clans in Karnataka. Further, important social portals and platforms, such as Conservationists and Ecologists Against Sexual Harassment (CEASE), highlighted the importance of a safe work environment within scientific fields, offering POSH Act 2013 guidelines. Another interesting display was the Conservation Society, India’s ‘BlueMAP-India’ project, a display that integrates art and policy to foster public engagement and conservation awareness.