For conceptual artist Lakshmi Madhavan, the gossamer fine cotton cloth woven with gold zari (kasavu) is her chosen medium to explore a people’s stories, culture and social mooring. The Mumbai-based artist uses the kasavu-bordered cotton textile to explore her identity, her roots and her efforts to bridge the different facets of her life while juxtaposing her quest with the lives of the weavers.

For the last five years, Lakshmi has been closely working with weavers in Balaramapuram, 19 kilometres from Thiruvananthapuram. The endeavour merges a personal quest with her artistic inspirations, “delving into the intersectionality of material, socio-cultural structures and gender codes,” says Lakshmi.

Her select works, Laboured Landscapes, were part of a group show, Three Steps of Land, at Los Angeles in the US. Curated by Rajiv Menon, the exhibition focussed on upcoming artists’ depicting Kerala or their idea of Kerala in different media.

Lakshmi Madhavan working on her installation ‘Hanging by a THread’ for the Lokame Tharavad exhibition at Alappuzha in 2021.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Lakshmi explains that although many artists have their roots in Kerala, they grew up outside the State. She says, “Like me, many of them are searching for an identity, for the ties that bind and separate us from our parents and grandparents.”

Her statement on her art says that her attempt has been to “reimagine the boundaries between art and craft, high and low art, domestic and public realms, feminine and masculine impulses and, instead, focus on the depth and the nuances of a complex, expressive practice,”

Lakshmi found her medium when she wanted to pay homage to her paternal grandmother who passed away in 2021. With the help of the cotton and silk threads of the kasavu cloth, she travelled back in time to study the history and heritage of the cloth. “It was for the show Lokame Tharavadu, curated by Krishnamachari Bose, that I designed six panels with letters of the Malayalam alphabet and words that, in some way, connected my grandmother and me.”

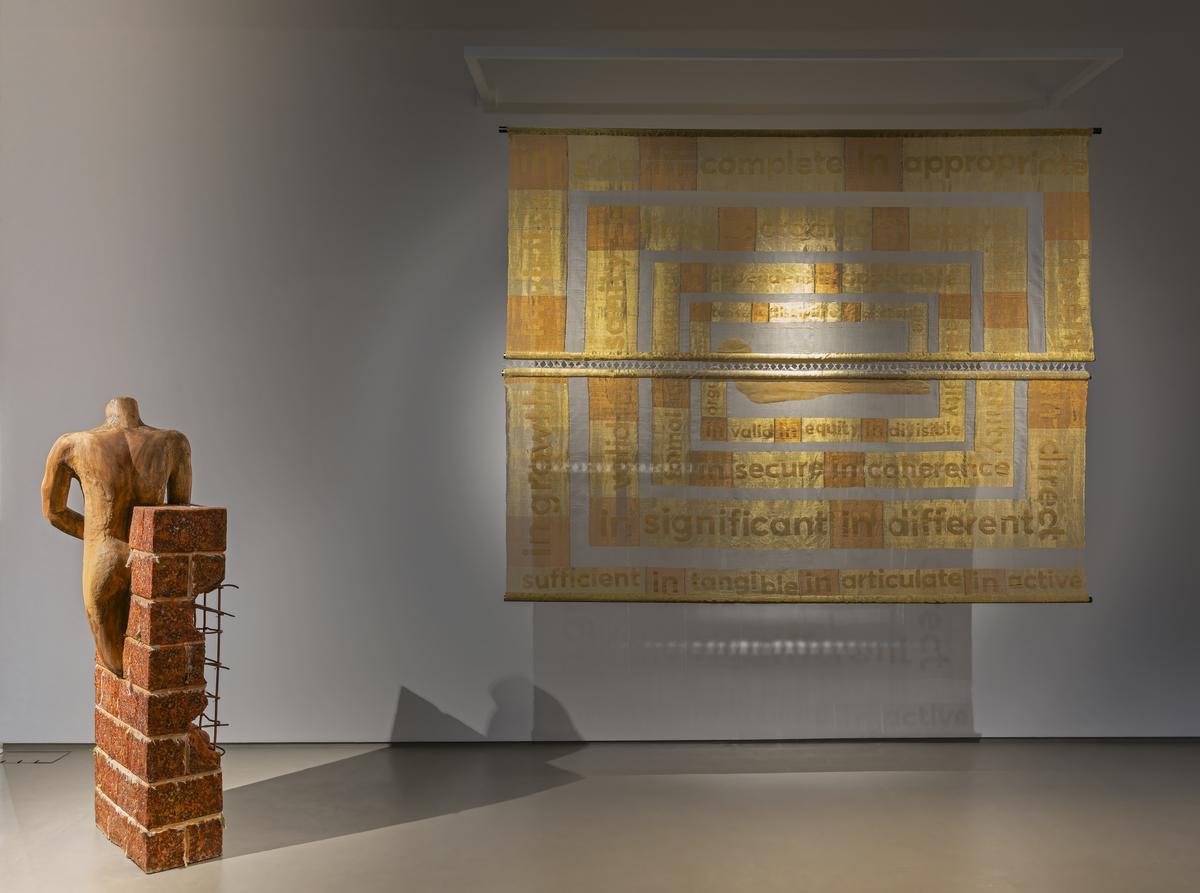

Lakshmi Madhavan’s works explores the many connections between body and cloth.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

The pristine cotton kasavu mundum-neriyathum symbolised her grandmother who only wore those. “Widowed early in life, she was always dressed in gold and white. It was not really by choice. Going by the social norms of those times, she could not wear bright colours, the karas and kasavus could not be very broad and so on.” Growing up around her, Lakshmi gradually realised that there is a “complex relationship between body and cloth. That is where my journey began.”

Through the woven panels of her work, Lakshmi examines ideas of identity, loss, connections, restoration and regeneration. “I feel that the weavers of Balaramapuram, as a community, are experiencing and investigating these ideas of identity and generational connections.” Lakshmi’s art with kasavu has evolved as she unearths the different facets of cloth and body and her Malayali heritage.

Lakshmi Madhavan, who has been working with Balaramapuram weaves and Kasavu for the last five years, held her first solo exhibition, Generations in My Body, at Akara Contemporary in Mumbai in 2024.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

The artist muses that it has been a journey that also motivated the weavers to rethink and reimagine what one can do with kasavu as a textile, as there has not been much of innovation.

“The most significant innovation has been that the two-part mundum-neriyathu becoming a sari. When I began engaging with the weavers, I had all kinds of requests. I wanted them to weave 7,000 letters, some in English, some in Malayalam; I wanted them to expand or contract the size of what they usually wove. I wanted to make switches within the thread, within the weave itself.”

It was also challenging for the artist to get the community to accept her and the weaving challenges she placed. She says, “For years, they have been purveyors of fine clothing and the best skilled weavers are 65-plus. To get them to learn or try anything new was an uphill task.”

Her work with the International Artists Collective, a studio and gallery in Copenhagen and her training with the German artist, Bernhard Martin at the Summer Academy in Salzburg have helped her gain new perspectives during her artistic journey. Jitish Kallat, curator and artistic director of the 2014 Kochi Biennale, has also mentored her in Mumbai. Her first solo exhibition was Generations in My Body, an exhibition at Akara Contemporary in Mumbai.

The roots of Balaramapuram

It was during the reign of Balarama Varma (1798 to 1810), ruler of erstwhile Travancore, that weavers from seven families of the Shalia community were brought from Valliyoor, in Tirunelveli district in Tamil Nadu, and resettled in Thiruvananthapuram to weave clothes for the royal family. Eventually, in the memory of the ruler, the place came to be called Balaramapuram.

“While working with the weavers and the cloth, I realised the multiple facets of cloth and body, as a societal marker with caste connotations, as an economic indicator and as a material with gendered stories.” She points out that the way the woven piece of cloth was worn defined a person’s place in society, her caste, religion and economic status.

Conceptual artist Lakshmi Madhavan’s works with Balaramapuram weaves and Kasavu to narrate stories on identity, roots, inheritance and loss.

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

“Although the weavers are from a community that was considered to be lower in the caste hierarchy, those supposedly belonging to the upper castes bought the cloth woven by them. But once the cloth left the loom, they could not touch the cloth worn by the aristocracy. They could not afford to buy it either!”

Narratives in art

Lakshmi was the artist in residence at the 2023 India Art Fair, Delhi. Her recent exhibitions include those at NGMA (Mumbai), National Museum (Delhi), Melbourne Museum (Melbourne), Hampi Art Labs (Vijayanagar), Craft Museum (Delhi), Kochi Muziris Biennale Collateral (Kochi).

Lakshmi recalls how a weaver had told her that he could never afford to buy the pieces he had been weaving for 30 years. Her attempt was to use the cloth to bring these narratives and understand the legacy of the cloth and its future. “As one of the few gender-neutral clothes in India, it was interesting to study how it has evolved over the ages. When the Europeans first came to Kerala, they found the mundu was worn by both men and women. And both were bare-chested. It was normal for a woman in Kerala to be bare-chested, whether you were royalty or commoner. I was interested in how that cloth, influenced by ideas of Victorian prudery, evolved. First came the melmundu to cover the chest and then the jumper or the blouse.”

A lot of these enquiries culminated in an exhibition that examines the politics of body and cloth. Even the word body is decoded through her questions about whether the word refers to a physical body or a community body. Could it be a caste body or a generational body? She says, “There are two parallel narratives— one is the story of the community in Balaramapuram and another is my own history, as being passed down generations.”

Using shuttles, threads and woven pieces of cloth, Lakshmi visualises her story and traces her quest while also narrating the story of the Balaramapuram weavers who are struggling to keep their legacy alive as their successors move away from the traditional occupation in search of greener pastures.

“My grandmother wanted me to keep my roots alive although I had lived outside Kerala. It is the same with the senior weavers in Balaramapuram who are trying to pass on their extraordinary skills and legacy to the younger generation.”

Published – October 08, 2024 11:46 am IST