Henrik Sorensen/DigitalVision via Getty Images

There’s a lot to be said for à la carte.

According to this site, this culinary approach “emphasizes personal choice and quality, ensuring guests enjoy a meal perfectly tailored to their tastes and desires.”

Put another way, you pay only for what you really want.

Cable TV subscribers, too, have long craved à la carte offerings. SNS (Studio Network Solutions) described how:

“[o]ne of consumers’ biggest beefs with cable TV is its bloat. That one channel we really, really want is, inevitably, buried inside a package with . . . a whole bunch of channels we don’t want.”

Hence, the cord-cutting binge. On February 26, 2023, zippia.com reported that “[c]able providers lost approximately 25 million subscribers since 2012.” (Bold face in original.)

Active stock investing is, essentially, classic à la carte. Own what you want, pay what you want, and do it all when you want.

That said, à la carte isn’t necessarily nirvana.

Menubly.com criticizes a la caret restaurant ordering for complexity, higher per-dish prices, inconsistent portion sizes and longer wait times for separately prepared plates.

For cable TV, SNS bemoans the way streaming services are reinventing what many hated about cable by priceyness, adding in advertising, and charging for networks rather than shows.

And surely, you don’t need me to tell you how many investors hate à la carte (active) stock picking. There have long been armies of academicians and ETF sponsors who’ve been more than happy to do that.

As a prototypical Libra, I tend to see “both sides of every argument.” So, I hesitate to pick à la carte or bundling as being definitively better.

Instead, my mission today is to present Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA) as an intriguing example of a Commercial-Venture, or “ComVen bundle.”

I just invented this phrase. But the idea has deep roots.

Developing the ComVen Approach

Stock prices don’t equal value. They equal value plus something else.

I got that from a 1984 paper, Stock Prices and Social Dynamics by Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller.

He describes two sources of demand for stocks.

Shilller calls one smart money investors. They buy based on value-relevant information subject only to wealth constraints. The others, ordinary investors, “do not respond to expected returns as optimally forecasted.” Put another way, the latter consists of all who aren’t smart-money investors.

Fisher Black (from the famous Black Scholes Merton option pricing model) had a less charitable label for ordinary investors. He described their impact on the market as “noise.”

Stanford’s Dr. Charles M.C. Lee put it in a more investor-friendly way. From his work, I got the equation: P = V + N, Price = Value + Noise.

We know price. And many investors estimate a stock’s proper value. The difference (P – V) is the portion of the stock price allocated to noise.

We can then evaluate the reasonableness of the noise component. Going back in time, I demonstrated how this could be done in a May 20, 2014, Seeking Alpha post.

And I found something more satisfying from just a bit before that, March 20, 2014. Using the value/noise framework, I published a Seeking Alpha article in which I said “Buy” for Tesla.

TSLA was then priced at $12.16. Today, it’s above $200.

I wasn’t able to work further on that framework while on my last full-time job. I had to use that company’s model. And based on that, I summarized a TSLA investment on January 11, 2023, saying “[n]o matter how great Tesla’s story is, it isn’t worth the stock’s current sticker price.”

That model made a bad call. Since then, TSLA has climbed 80%. The Invesco QQQ Trust rose 67%. The SPDR® S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY) has gained 40%.

Now, I’ve been in this business too long to gloat over results during any one specific period. Different periods may produce different outcomes. For all I know, my current recommendation for TSLA may fall flat for a while. (My last super-success occurred over 10+ years!)

I should add that I consulted in the development of the model that misfired on TSLA in early ’23. But now that I’m back on Seeking Alpha – and this time semi-retired and truly independent – I want to go back to refining a framework in which I truly believe.

My last company was one of many that used a factor model. As those go, the one we used was pretty decent in its day. But models like that can’t really account for the split personalities inherent in stocks. The value/noise approach does that.

And I want to adapt it to today’s world. I would like to use it to make sense of super-tech, AI, and I’ve dabbled in and will continue with Biotech.

I wish to help you make sense of what you’re seeing with so many hard-to-explain stock prices. And I intend to help you cut through the dire rhetoric from those eager to dance on the graves of AI and other such things. (Here’s an example.)

Introducing the Tesla ComVen Bundle

Updating the value/noise labels seems apt.

I’ll replace Value with Com. That stands for commercial. This part of a bundle consisting of the company’s regular commercial efforts. For Tesla, it’s the basic electric vehicle (“EV”) business.

Instead of saying Noise, I’ll say Ven. That refers to venture. This is future-oriented.

We can’t value venture precisely. We’re mere mortals, and can only project or assume what will happen tomorrow. But we can’t know. We may find quantitative clues. But ultimately, we’ll have to lean on common-sense and business judgment.

The essence of equity investing requires Ven.

If you’re only going to buy the present, you should stick with fixed income. That will usually present much better reward-risk profiles.

For many companies, the Ven component is typically in line with general business growth. In such cases, it wouldn’t be the end of the world if you don’t bother to think about the full ComVen bundle.

Nvidia (NVDA) is an example of a stock that requires this. I explained why regular valuation models for that are useless. And I’ll return to NVDA in the near future. But today, I want to revisit my old 10-plus bagger (nearly 20-bagger), TSLA.

For Tesla, CEO Elon Musk epitomized its venture element when he said the following during the company’s July 23, 2024, earnings call:

[T]he value of Tesla overwhelmingly is autonomy. These other things are in the noise relative to autonomy. So, I recommend anyone who doesn’t believe that Tesla will solve vehicle autonomy should not hold Tesla stock. They should sell their Tesla stock. You should believe Tesla will solve autonomy, you should buy Tesla stock. And all these other questions are in the noise.

Musk suggested Venture, with a capital “V”!

Once upon a time, this sort of thing would have been confined to angel investing or venture capital.

That’s no longer the world in which we live. Venture capital is often looking to exit earlier. IPOs help them do that.

That means the stock market has plenty of companies for which the old noise component of price more closely resembles what in a bygone era might have been an early-stage pre-public company. Case in point: Tesla’s efforts to solve vehicle autonomy.

So let’s now consider each component of Tesla. I’ll start with what many will consider familiar ground…

TSLA’s Commercial Component

This is a well-covered company. So, I’ll just summarize rather than recount all the details.

Tesla is the pioneer and leader when it comes to EVs.

It wasn’t formed because somebody crunched a spreadsheet and calculated an attractive Net Present Value. (Shades of business school finance!) Walter Isaacson’s September 2023 Elon Musk biography shows in great detail Musk’s commitment to climate change and renewable energy. He was deeply into it long before ESG became a thing.

We already see electronic vehicles gaining ground in the U.S. and elsewhere. To some degree, it’s consumer choice. But there’s a lot of regulatory pressure for this at federal and state levels.

It’s not a smooth upward-pointing line. Cost (these things are expensive) and battery life/charging pose challenges.

Too, politics and physics share something in common. Action provokes reaction. And there’s plenty of that with EV regulation. (See, for example, here, here and here.)

Add in increasing competition. (Other Domestic automakers are also making EVs now. So too are foreign companies, especially in China.) Stir in increasing uncertainty about the ability and willingness of consumers to keep spending now. Top it off with Tesla’s current determination to offer more affordable EVs.

The result is a nice growth business, but one which right now is slumping.

That’s OK. The auto business has always been cyclical and still is. And we embrace newness in fits and starts. Pioneering businesses typically offer, learn, correct and improve as the newness transitions to typical.

Recall how much discovery, whining, correcting and enhancing it took for today’s digital devices to become what they now are. And with AI emerging, we’re not done yet. It’s the same with EVs.

Through it all, Tesla has a distinct edge. Isaacson recounts, in detail, Musk’s fanatic Steve Jobs-like attention to the details of product.

K.K., a former colleague, current friend, and hopefully future Seeking Alpha analyst, shares her father’s opinion of Tesla’s product. According to him, those who dislike Teslas are those who don’t own them.

Is Papa K an eccentric oddity? Maybe. But consider the numbers I’ll present below. As you do, recognize the Tesla got where it is without advertising! Imagine competitors, who spend to the hilt to advertise, would react if one suggests they drop their ad budgets to zero.

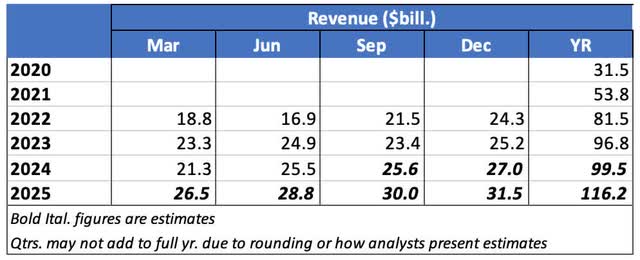

In the trailing 12 months, Tesla generated $95.3 billion in revenues.

That pales compared to Toyota (TM), Ford (F) and General Motors (GM). Over that same span, their revenues came in at $288.4 billion, $180.4 billion and $178.1 billion.

But TM, F and GM are long-time well-established companies. Tesla didn’t sell anything before 2008, And that was a high-priced sports car. Its first mainstream offering came in 2012. And remember: Unlike its peers, Tesla doesn’t advertise!

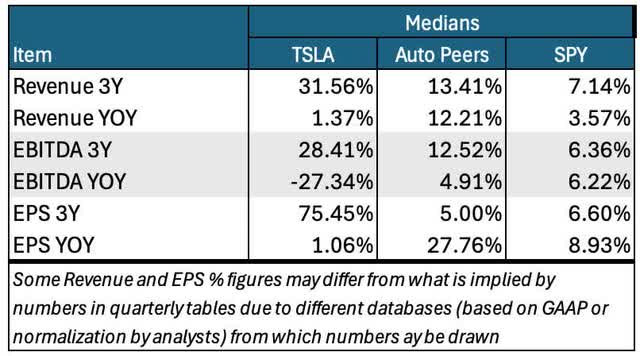

Keep that in mind as you look at the following growth trends

The Peer comparison includes most companies in the Seeking Alpha Automobile Manufacturers Industry. I just omitted a few that don’t make recognizable-brand vehicles.

(And as usual, I compare companies to benchmark medians. These aren’t impacted by wild distortions often caused by unusual data items, that, even in big companies, can dominate weighted averages.)

Analyst’s computations and summary from data displayed in Seeking Alpha Portfolios Analyst’s computations and summary from data displayed in Seeking Alpha Portfolios Analyst Compilation based on Data from Seeking Alpha Earnings and Financials Presentations Analyst Compilation based on Data from Seeking Alpha Earnings and Financials Presentations

We see that Tesla’s having a down year. And its margins are really tanking. Besides the current challenges identified above, Tesla has one more. It’s working hard to sell more cars at lower price points than before.

Yes, we’re investors. We’re supposed to hate plummeting margins. But let’s not get crazy. Ultimate profitability (returns on a capital base) combines margins and turnover. The latter relates to volume.

To become a true grownup auto company, Tesla must sell more cars to a broader customer base. That means more lower-priced models; i.e., more volume and less margin. So, Tesla has to do this and let margins slide, investor opinion be darned. (This sounds a bit like the Aamzon.com (AMZN) story. That worked out pretty well!)

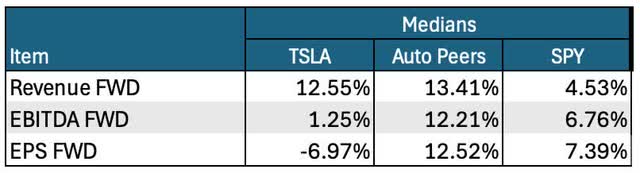

Here’s the overall fundamental picture.

Analyst’s computations and summary from data displayed in Seeking Alpha Portfolios

Notwithstanding cyclicality and other challenges, two things are clear.

First, Papa K (referred to above) is not alone. Plenty of other people love their Teslas.

Second, Tesla is a very substantial and valuable commercial enterprise.

TSLA’s Venture Component

Now we’re talking about dreams, aspirations, ideas, etc.

Nothing here is quantifiable. If it were, we’d be able to call upon ordinary valuation techniques.

You may have heard about things like the Rule of 40. Supposedly, private equity investors want the year-to-year growth rate of recurring revenue plus the EBITDA margin to total at least 40%.

Don’t take that too seriously. It’s just an informal rule of thumb.

It doesn’t spring from financial theory. (Even the famous PEG ratio rule of thumb has some connection to theory: Higher growth justifies higher P/Es, but even here, the ratio fails to account for a discount rate.)

And the numbers it uses don’t necessarily apply to pure venture. Private equity often invests in bona fide commercial enterprises that have meaningful numbers such as these.

When we get right down to it, pure venture, sans conventional metrics, boils down to judgments about the company’s aspirations and clues suggesting whether the company has a credible chance of making big things happen.

Full vehicle automation – no steering wheels, no gas pedals, no brakes, no humans changing gears, would be revolutionary. We don’t have it yet. Most autonomous vehicles with which we’re fiddling still allow for some human override.

But Tesla wants to be the one to make full automation real.

The accomplishments of Musk and his team suggest they have a more-than-theoretical chance of success.

We already know that the team succeeded in pioneering EVs, at scale and now at increasingly affordable prices. And they’ve been doing so without blowing up the company. (See the fundamentals chart above.)

SpaceX (SPACE) is an independent company. But there’s an enough human crossover, especially since Musk is the guiding light for both, to make it a relevant indicator of Tesla’s capabilities.

It’s assumed leadership the rocket launch. And it clobbered long-time contractor Boeing to accomplish that. SpaceX has been able to live with fixed-price contracts. Boeing is at its best with cost-plus contracts that let it propel its, and NASA’s, costs up into orbit.

SpaceX subsidiary Starlink’s communications/internet satellite constellation started with 10,000 customers in 2021. It now has about 3 million. On May 8, 2024, Starlink soars: SpaceX’s satellite internet surprises analysts with $6.6 billion revenue projection reported “mind-blowing” accomplishments and a likely “staggering $6.6 billion in revenue for 2024.”

Tesla’s AI humanoid Optimus robot has yet to garner universal praise. But these are still early days. We can say the same for The Boring Company, a SpaceX subsidiary aims to bore tunnels (to ease surface traffic woes) better and cheaper.

Musk was a co-founder of OpenAI. Now, he’s trying to build xAI to compete in the field.

We can’t say everything (beyond Tesla, SpaceX and Starlink) will succeed. But such risk is inherent in venture investing.

Here, however, we do at least see powerful indicators of product development prowess for Musk and his team. And in the cases of Tesla, SpaceX, and Starlink, the Musk team succeeded in building to scale… and for TSLA at least (the only publicly owned company), strong returns on equity.

So I think Musk has a credible chance to truly solve vehicle automation. Extrapolating the dream full out, that could mean no more private vehicles.

Everybody would summon the robotic vehicle they need when they need it and pays (to Tesla, of course) only for use. (So it’s more than merely selling robotaxis to ride-sharing services.) Solving robotics (Optimus) would be a heck of an add-on, in the factory, in the household, on construction sites, etc.

As ventures opportunities go, this one is looks impressive if you can handle the risks.

Risks

Technological disappointment is an obvious risk. (See, e.g., The Boring Company, Optimus).

Financial risk isn’t as horrid now as it once was. On many occasions in the past, Tesla was within a whisker of running out of money. Ditto his other ventures. But at least for now, Tesla’s finances have become respectable.

Then, too, there’s Elon Musk himself.

He’s got a strong technical background and is not a numbers cruncher. He is very much a hands-on CEO.

That’s great from a product-operations-design vantage point. But with all his activities, Tesla and otherwise, he risks spreading himself too thin.

And he’s the human embodiment of political/image risk. The SEC wasn’t thrilled about Musk first tweeting about his desire to buy Twitter. His battles with X (formerly known as Twitter) employees and advertisers are the stuff of legend. And now in Brazil, he’s taking on a government.

And, of course, he’ll need to keep attracting people willing and able to handle his sometimes-harsh management tendencies. Isaacson’s biography (page 377) quotes Musk as telling a Saturday Night Live audience:

To anyone I’ve offended, I just want to say, I reinvented electric cars and I’m sending people to Mars in a rocket ship. Did you think I was also going to be a chill, normal dude?

Finally, there’s the “key man” question. If, for whatever reason, Musk can’t continue on at Tesla, can someone else pick up the slack? (Have others already been doing more than the public realizes?) We can’t know ahead of time… but with as much as Tesla has done, it’s difficult to believe it’s a complete one-man show.

What to do About TSLA Stock (the full ComVen Bundle)

The traditional ratios are way out of proportion to what TSLA’s commercial component alone is worth today.

Analyst’s computations and summary from data displayed in Seeking Alpha Portfolios

That’s the same conclusion I reached with the different model on 1/11/23.

Today, for a back-of-the envelope valuation of Tesla’s Com portion….

I’m going to use the Proj. 3-5Y EPS Gr we see above. But I’ll deflate the PEG FWD to 3.00.

My PEG assumption is still relatively high. But it’s not outrageously so, especially since I think TSLA’s core business can outperform the consensus growth projection.

That puts the Com valuation at about $80 per share. (Don’t try to replicate the exact math. My analyst days started in 1979. I grew up thinking the current practice of not rounding projections like this is madness!)

This means about $150 of the stock price (or about $460 billion worth of market capitalization) is attributable to the Venture, “unicorn,” portion of TSLA.

That’s a lot. But consider…

Crunchbase puts the valuation of unicorn ByteDance at $220 billion. Venture Tesla is staring at a much bigger potential business and a vastly stronger competitive position. (Tell the truth, as you scroll social-media videos, don’t you often lose track of whether you’re on TikTok or Instagram Reels. I do.)

The same source values SpaceX at $125 billion. It’s a fascinating business. But when it comes to reach, to addressable market size, I have to believe that Venture Tesla’s potential enterprise should be more than 3.7 times the size of SpaceX.

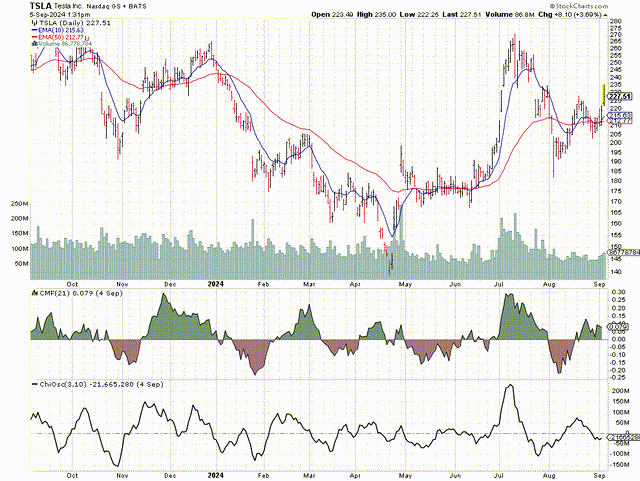

The price chart is interesting.

According to basic chart analysis (the way I do it), that’s a nothingburger.

But think back to those valuations I showed you earlier. Now ask yourself… Why doesn’t the chart look much worse, considering TSLA’s ongoing cyclical and competitive challenges?

Looks to me like many others in the investment community are noticing, and putting money into, the venture aspect of TSLA. That seems so even though others aren’t verbalizing it the way I do here.

As I’ve said before, my investment stance depends mainly on whether I think a stock will be better than, in line with, or worse than the market.

Here’s how I apply that to the Seeking Alpha rating system:

- “Strong Buy” means I see the stock as being better than the market, and I’m bullish about the direction of the market.

- “Buy” means I see the stock as being better than the market, but am not confident about the market’s near-term direction.

- “Hold” means I see the stock as moving in line with the market.

- “Sell” means I see the stock as being worse than the market, but am not confident about the market’s near-term direction.

- “Strong Sell” means I see the stock as being worse than the market, and I’m bearish about the direction of the market.

Based on this scale, I’m rating TSLA as a “Buy.” But I do so only for those who can handle the Venture risks.

Note, too, the necessary time horizon. Stocks like this aren’t for people who obsess over every quarter and on changes in guidance. Remember, my last and super-successful TSLA recommendation was more a decade ago. And it took about five years for the stock’s biggest rally. So, when I say long term here, I’m not just repeating a popular cliché. I really mean LONG!