More than 50,000 spectators filled Kennedy Stadium in Washington on Nov. 27, 1977, for a football game between two bitter rivals, the Washington Redskins and Dallas Cowboys.

There was drama in the game, with both teams in the hunt for a playoff berth, but more unusual was the entertainment before and at halftime: an enormous spectacle of Native American music, dance and history. It was, The Washington Post reported, “part of a new movement to re-establish American Indians as first-class citizens in the United States.”

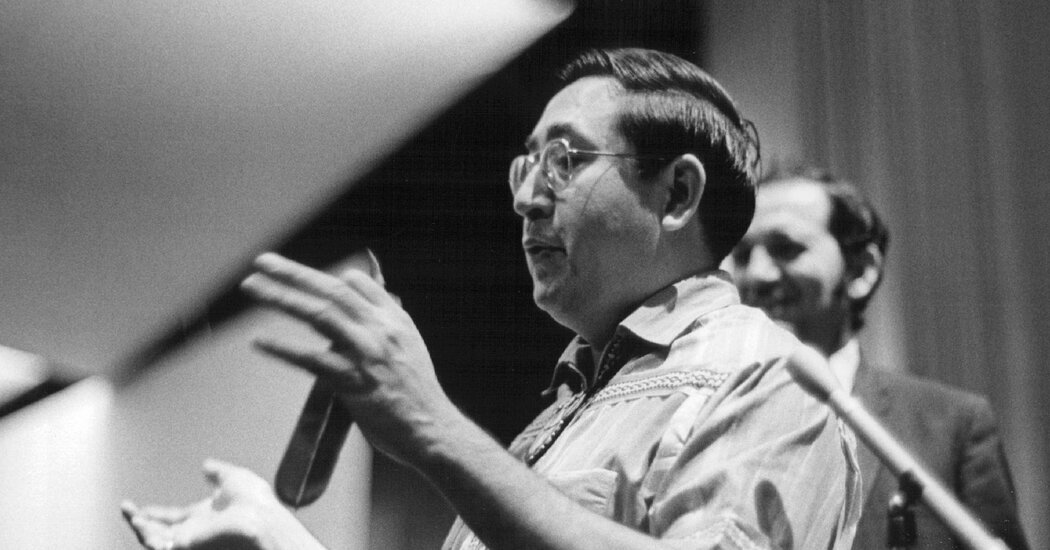

At the center of the event was the National Indian Honor Band — 150 students chosen from 80 tribes in 30 states — which played four pieces by Louis W. Ballard. With tens of thousands of listeners, this was probably the most prominent platform a Native American composer had ever had.

The performance was a career highlight for Ballard, a pioneering figure who paved the way for the broad upswing in Native composers over the past few decades. He was among the first to negotiate issues that younger artists still face: melding Native and Western classical traditions; the role of his music in social and political activism; expressing his community’s deep history and culture in a modern way.

“Ballard was the grandfather of Native American composers,” Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate, one of that next generation of artists, said in an interview. Tim Long, a conductor and teacher, echoed that sentiment: “He is the father of all of us who are Native people in classical music right now.”

A composer as well as a pianist, conductor, filmmaker, writer, teacher, compiler of Native songs and national curriculum specialist for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Ballard had his music performed throughout the United States and Europe. He studied with Darius Milhaud and brought Stravinsky to a ceremonial Deer Dance in New Mexico.

But Ballard has not gotten his due. Only a limited amount of his work was commercially recorded, and even less remains in print. When he died of cancer in 2007, at 75, he had no obituary in The New York Times or other major publications. His pieces are infrequently performed.

This is part of the persistent invisibility of Native Americans and their culture. It is telling that CBS was supposed to include that 1977 halftime performance in its national telecast but didn’t. (And yes, today it is eyeroll-inducing that the game was a showdown between the Cowboys and Redskins, who are now the Commanders after a long battle over their insensitive name.)

In 1960, at the start of his career, Ballard wrote, “Indian music still awaits a rescue from oblivion to take a place in the cultural milieu.” In many ways, that wait continues.

There has been some heartening interest in Ballard, though, particularly since the murder of George Floyd in 2020 turned the attention of many in the cultural world to artists from long-marginalized backgrounds.

Ballard’s family started a website that offers a valuable introduction to his life and music. In 2023, an album on the Naxos label provided a rare hearing for some of his orchestral works. And last summer, at an audience-participation event at Lincoln Center, more people voted for Ballard’s burning 1974 piece “Incident at Wounded Knee” than for Haydn.

The 15-minute “Incident” is a good place to start with Ballard, though it is widely accessible only through an archived video of a 2022 performance by the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, which commissioned it.

The title refers to the 1890 massacre of Native Americans by Army troops at Wounded Knee Creek on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. But the piece was also written in the wake of the two-month occupation of Pine Ridge in 1973, a protest of conditions on the reservation.

Ballard “gathered himself to really deal with this theme,” Dennis Russell Davies, St. Paul’s conductor at the time, says in a recent interview on the orchestra’s website. The piece, as so often with Ballard’s work, is rhythmically angular, the mood evocative of a kind of stylized violence that is broken by episodes of grave mournfulness.

The second movement, “Prayer,” starts with an elegy for cello and oboe, around which the rest of the orchestra chimes in with passionate assent. The next two sections are fiercely punchy, though in the fourth, “Ritual,” the ferocity lets up at a cliffhanger moment before building back up; Ballard had an instinct for pacing.

As was his general philosophy, he avoided quoting traditional melodies in “Incident.” “Indian music today is very difficult to authenticate and a composer errs in trying to imitate themes or melodic germs,” he wrote about a decade before composing the work. “What I seek is a reincarnation of the character and spirit of the aboriginal music in standard notation.”

“Incident at Wounded Knee” is characteristically Ballard: Its style is modernist, but not austere. He had a taste for sumptuous, even melodramatic effect, which led some critics to compare his work to overblown movie music. “Incident” is written for a standard chamber orchestra, but many of his pieces bring together traditional Native instruments — particularly percussion and flute — with Western ones.

Though his inspirations were often folk tales and Native history, he was insistent that he did not want to plainly depict these stories, but rather to use a wide range of tools, both traditionally Native and Western classical, to convey more abstractly a sense of his experiences and heritage.

“What I am attempting in my music,” he wrote, “is to express my creative impulses in such a way that my identification as an Indian with a deep cultural heritage and background will enrich my contribution to the musical art.”

No biography of Ballard has been published, but there are useful materials around, including a thoroughly researched 2014 dissertation by Karl Erik Ettinger. Ballard was born on July 8, 1931, on the Quapaw reservation in the northeastern corner of Oklahoma. His mother was Quapaw; his father was Cherokee.

His earliest musical experiences came from attending ceremonial powwows with his father and taking music lessons from his mother. When he was 6, he was sent to a government-operated boarding school that was harshly repressive of students expressing Native language or culture. Music ended up a lasting refuge.

“The piano became my surrogate mother and father,” he said. “It was reliable; it was always there.”

He excelled at school through college at the University of Tulsa. After graduating, he found jobs at churches and as a school music teacher. He was making so little money, though, that he started at Tulsa Technical College, planning to become a mechanical draftsman. Miserable, he returned to the University of Tulsa for his master’s degree.

His early works established what would become his standard practice: employing what he called “modified atonality” (distinct from pure Schoenbergian serialism), a strong rhythmic profile and the combination of instruments from the “two worlds” he inhabited.

“In my music,” he wrote, “I have sought to fuse these worlds, for I believe that an artist can get to the heart of a culture through new forms alien to that culture.”

“Peyote” (1960) was among his first attempts to bring together Native elements and Western composition; it was written for trumpet, French horn, trombone, piano and two Native percussion instruments, water drum and gourd rattle. His brief yet bold Four American Indian Piano Preludes, which have been stylishly recorded by Emanuele Arciuli, allude to Native drumming, singing and flute playing. After Ballard finished them, Milhaud told him, “Louis, you are a composer now.”

In 1965, he married Ruth Doré, a pianist who became his strong-willed manager and indefatigable publicist. Two years later, for the 60th anniversary of Oklahoma’s statehood, he wrote the ballet “The Four Moons,” which was danced by a quartet of important ballerinas of Native descent from the state: Yvonne Chouteau, Rosella Hightower, Moscelyne Larkin and Marjorie Tallchief, who had an elegantly longing solo.

The sections of “Cacéga Ayuwípi” (“Decorated Drums” in the Sioux language, and written in 1970) were inspired by the rhythms of songs from different tribes. The instrumentation includes Haida, Hopi and Yaqui rattles made from turtle shell, glass, skin and metal as well as Ute and Apache bull-roarers, whips, an eagle-bone whistle and notched sticks.

Ballard was at ease in the unofficial position he assumed late in his life as a mentor and role model, a regular presence at concerts by younger Native artists. “He knew how important that was,” Long said. “He was always there as our steady support. Simply seeing him there in his wheelchair gave us a real sense of safety.”

In the 1980s, his works began to focus more on Western instruments. His piano pieces took on the flair of a composer who was also a virtuoso player, particularly a triptych of “City” pieces that began with “A City of Silver,” a fantasia on precolonial South America.

Those three pieces deserve a place on concert stages, and his six “Fantasy Aborigine” works for orchestra should also be heard. “Incident at Wounded Knee,” perhaps Ballard’s most important and well-traveled success, sorely needs a broadly available audio recording so many decades after it was written.

The St. Paul Chamber Orchestra gave it many outings, including on a European tour. In its pain but also its evocation of survival, its sense that a better future could be forged through mutual respect and cultural encounter, the piece summons all of Ballard’s hopes for his nation.

“The fact that I was taking a bow onstage with a white American orchestra and conductor,” he recalled of that European tour, “did more than words can to show that we live in a free country.”