On Aug. 30, 1892, the Western Reserve, a state-of-the-art ship en route to Minnesota, found itself in the middle of a gale in Lake Superior. Capt. Peter G. Minch, a millionaire shipping magnate traveling with his family, had been assured that the all-steel steamship would be safe and nimble on the seas. But the storm overtook the vessel, breaking it into pieces in the dead of night.

The ship’s crew and passengers boarded two lifeboats. One overturned almost immediately, and its crew disappeared. The other bobbed in the darkness for about 10 hours. Another ship passed, but despite screams for help, it continued its course.

As the lifeboat neared land, it overturned again. A crew member was the only person among the 28 who had been on the Western Reserve to make it to the Michigan shore alive.

On Monday, more than 132 years after the Western Reserve went down, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society announced that researchers had discovered the wreck of the ship, which was among the first all-steel steamships. Using sonar technology, they worked for two years before finding it about 60 miles northwest of Whitefish Point, a cape in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. It was near where the ship’s sole survivor, Harry W. Stewart, had estimated that it had foundered.

“This is probably one of the most important shipwrecks this organization has ever found,” said Bruce Lynn, the executive director of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum run by the historical society in Paradise, Mich. “It’s astounding.”

The Western Reserve, a fast ship personally captained by a leading industry magnate, was revolutionary at a time when wooden steamships were still the dominant freighters on the Great Lakes. “The Western Reserve was even called the inland greyhound because it was so fast from port to port,” Mr. Lynn said.

The historical society has for years surveyed the lakes to rediscover the myriad ships wrecked in its waters. The researchers divide the lake floor into a grid to systematically search for shipwrecks. Every year, the society patrols the waters with the David Boyd, a decommissioned U.S. Army Corps of Engineers research vessel, hoping for more finds.

Search days can be long and grueling, and the researchers typically find nothing on most voyages, Mr. Lynn said.

“A lot of coffee, a lot of doughnuts,” said Mr. Lynn, explaining the search routine. “The chitchat dies out after eight hours, nine hours out there.”

The David Boyd is equipped with side-scan sonar. The technology uses sound waves to construct images of the lake floor and can identify large aberrations on the flat surface, such as a shipwreck.

Darryl Ertel, who directs the society’s marine operations investigating shipwrecks, and his brother, Dan Ertel, searched for the Western Reserve for two years.

One day in July 2024, the Ertels noticed the sonar picking up something unusual 600 feet below the surface of Lake Superior.

“We side-scan looking out a half mile per side, and we caught an image on our port side,” Darryl Ertel said in a news release. “It looked like it was broken in two, one half on top of the other.”

They were excited that they found a shipwreck. But which one? They took its measurements and, sure enough, it was a match for the Western Reserve.

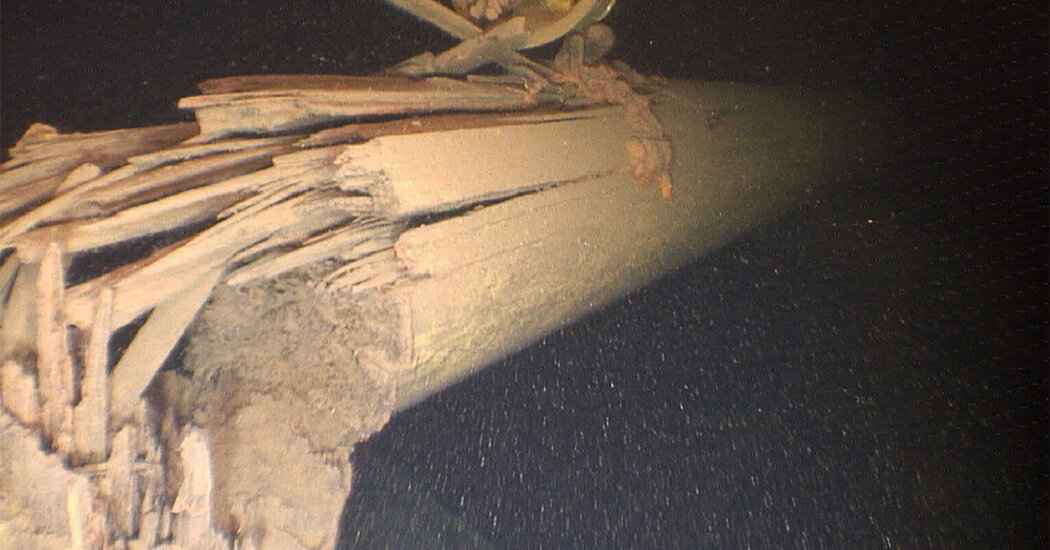

A week later, the Ertels and other crew members sent a remotely-operated submersible to survey the shipwreck up close. It was “in amazing condition,” according to Mr. Lynn. They took more measurements, which helped confirm the ship’s identity.

Mr. Lynn said the society did not publicly announce the discovery until it had made contact with descendants of Captain Minch, a distant relative of the Steinbrenner family, which owns the New York Yankees.

The steel ship, which was 300 feet long and 40 feet wide, was built in Cleveland for Captain Minch two years before he led its final voyage.

Mr. Lynn said that finding a shipwreck is often dependent on both luck and the right weather conditions. Mr. Lynn said that bad weather in 2024 limited their search, but the Western Reserve was a rare bright spot.

It is believed that there are thousands of wrecks in the Great Lakes, a heavily traveled shipping area between the Midwest and Ontario, Canada.

Advances in nautical technology have made locating shipwrecks in the Great Lakes easier. Researchers have increasingly discovered them, such as a schooner that sank in 1893 and was found last year, and a fleet of lumber ships that disappeared in 1914 and were discovered in 2023.

After thoroughly documenting the Western Reserve’s shipwreck, Mr. Lynn said, the museum plans to create an exhibit and a documentary about the steamship.

Michigan law makes it illegal to raise most shipwrecks. The researchers do not plan to raise it — that would be like disturbing a grave, Mr. Lynn said.

Before it sank, the Western Reserve was traveling to pick up cargo in Two Harbors, Minn., a port serving the so-called Iron Range, iron-ore mining areas around Lake Superior.

Experts disagree whether the Western Reserve’s construction or design contributed to its breakup in the gale.

A ship of similar design that was built by the same Cleveland shipbuilder, the W.H. Gilcher, foundered amid a gale on Lake Michigan, just months after the Western Reserve sank in 1892. The shipwreck of the W.H. Gilcher has yet to be found.