In the Late Cretaceous period, a remarkable flowering of horned dinosaurs occurred along the coastal floodplains of western North America. Two different families — each sporting every imaginable combination of spikes, horns and frills — diversified across the landscape, using their headgear to signal mates and challenge rivals.

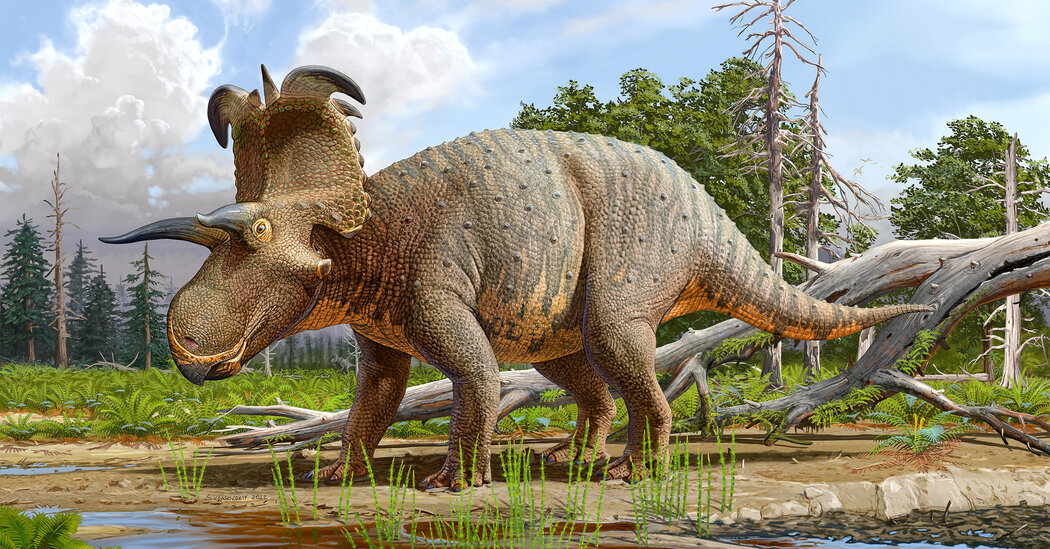

Seventy-eight million years later, members of that ancient profusion are still turning up, leading to a modern boom in discoveries. The newest — described on Thursday by a team of researchers in the journal PeerJ — is Lokiceratops rangiformis, a five-ton herbivore with spectacular, curving brow horns and huge, bladed spikes on its meter-long frill.

The researchers argue that this is a new species, and with others like it suggest that the area from Mexico to Alaska was full of pockets of local dinosaur biodiversity. Other experts, though, contend that there is not enough evidence to draw such conclusions based on one set of remains.

The skull of the dinosaur in question was discovered in 2019 by a commercial paleontologist on private land in northern Montana. It was acquired by the Museum of Evolution in Maribo, Denmark.

“They saved it by purchasing it, so now it’s available in perpetuity for scientists to look at it,” said Joseph Sertich, a paleontologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and an author of the study. “We couldn’t write a paper on a fossil sitting in a rich person’s living room and being treated as art.”

The team of researchers initially believed they were working with the remains of a Medusaceratops. But as they clicked together pieces of the shattered skull, they began to notice differences.

The animal lacked a nose horn. The brow horns were hollow. Then there were the curving paddle-like horns on the back of the frill — the largest ever found on a horned dinosaur — and a distinct, asymmetric spike in the middle.

“That’s when we really started to get excited,” said Mark Loewen, a paleontologist at the Utah Natural History Museum and an author of the study. “Because it became clear that we had something new.”

Because the skull was bound for a museum in Denmark, the team named the animal after the Norse god Loki. “It really does look like the helmet that Loki wears,” Dr. Loewen said.

The discovery sheds light on the evolution of North America’s horned dinosaurs, Dr. Sertich said. During the late Cretaceous, the continent was split in half by an inland sea. Two groups of horned dinosaurs ranged the western subcontinent of Laramidia. Chasmosaurines — the family that eventually gave rise to Triceratops — tend to appear in the southern half of the subcontinent, while Centrosaurines — the family that Lokiceratops belongs to — generally are found more to the north.

Lokiceratops is the fourth Centrosaurine found from its Montana ecosystem.

Remains of these species have not been found in other parts of North America, fitting a broader pattern of horned dinosaur diversity in the West, the researchers say.

“We’re not finding animals that lived in Canada in Utah, or animals that lived in Utah in New Mexico,” Dr. Loewen said.

The team suggests that dynamic might have been driven by sexual selection, with different populations of female horned dinosaurs developing specific aesthetic tastes that drove explosions in local species evolution. In modern ecosystems, that process has led closely related birds of paradise to develop different displays while sharing ecological niches.

By the very end of the period, the Centrosaurines had largely vanished, and animals like Triceratops and T.rex ranged from Mexico to Canada, suggesting a much more homogenous continent, Dr. Sertich said.

“It does have implications for the modern world — as we warm and change climate, animal distributions are changing,” he added. “Studying past climates and ecosystems and how they reacted is going to impact our understanding of what’ll potentially happen moving forward.”

Not everyone shares this explanation or believes that animals like Lokiceratops represent distinct species. Denver Fowler, a paleontologist at the Dickinson Museum in North Dakota who was not involved in the research, said that many ceratopsian species have been based on limited remains, leading to the potential for overinterpretation.

The hollow brow horns found in Lokiceratops, for example, are also present in the oldest adult Triceratops, he said, while the asymmetrical horn spike on the frill could be a quirk of genetics.

“A lot of the features here could just be signs of a very mature Medusaceratops, and that would be the more conservative explanation,” Dr. Fowler said.

Dr. Fowler and some of his colleagues favor another proposal: fewer species with more individual variation that shifted gradually from Mexico to Alaska. As more fossil remains come to light, it will become clearer which differences are significant, he added.

“It’s a spectacular specimen, and it absolutely needs to be described,” Dr. Fowler said. “It really helps us to flesh out the fauna.”

As more remains appear, Dr. Sertich said, teams will be able to test whether Lokiceratops is its own species.

“I can think of eight undescribed species coming soon,” Dr. Loewen said. “I don’t think we have 1 percent of the true Ceratopsid diversity that lived in North America.”